|

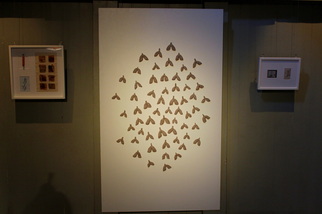

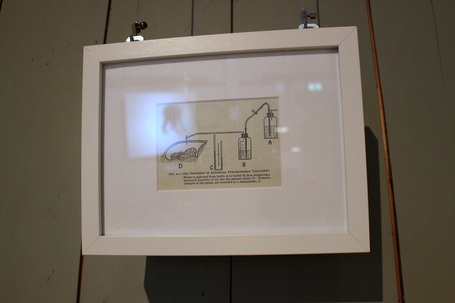

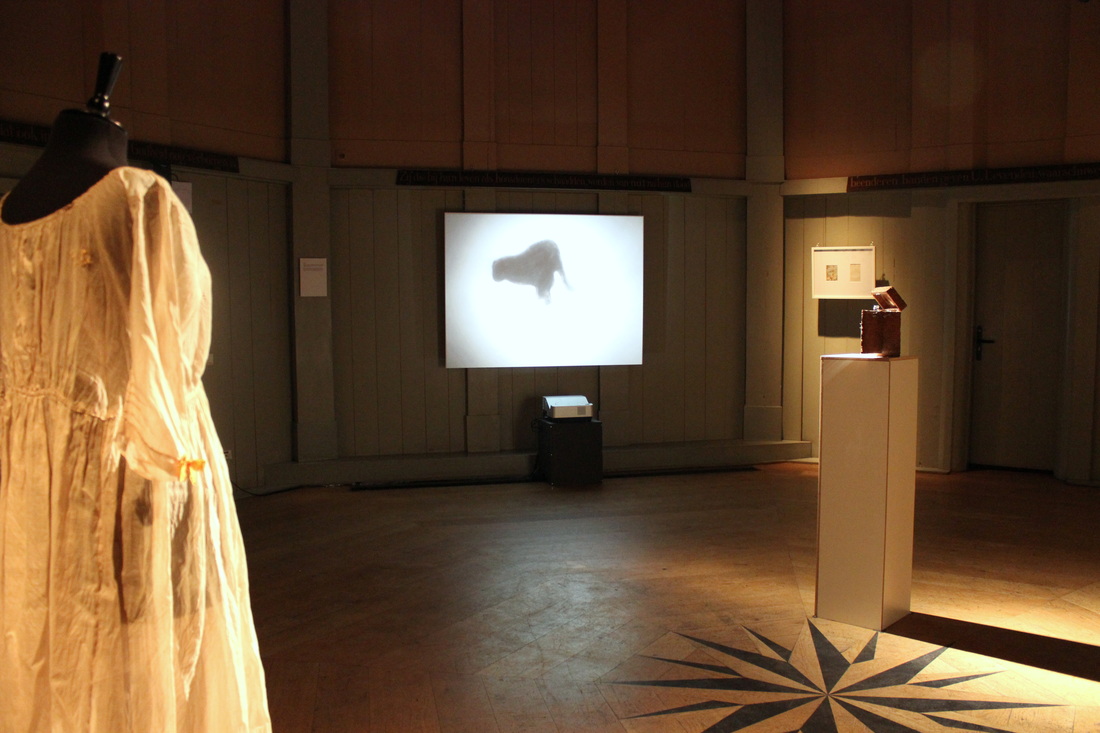

Anna Dumitriu explains the stories behind her exhibition here I’m in a room with humanity's biggest killer. It began eating away at us over 9000 years ago, and has never really stopped. The marks of our relationship surround me in an array of medical leaflets and dyed fabrics. Mysterious objects sit on stands. A glistening set of metal needles and devices inside a spongy wooden case. There's a tiny, bare bed, and a ghostly pale dress. A collection of tiny felted grey lungs that resemble a group of settled moths on a wall. This is an exhibition on tuberculosis. 'The Romantic Disease' has been created by Anna Dumitriu, a British artist with a taste for microbiology and emerging technologies. She is the artist-in-residence for the Modernising Medical Microbiology project, a collaboration between Oxford University and Public Health England, and she was inspired to create this exhibition by their research into bacterial diseases. The exhibition is on tour through Europe, and is currently hosted in the Theatrum Anatomicum at Waag Society in Amsterdam.  What caused tuberculosis? On one side of the room I see an animated black dog circling and pacing endlessly. It represents one early interpretation, the 'demon dog'. This dog would enter the bodies of sufferers and bark, making them cough. Later, people thought tuberculosis could be inherited. On another wall I read an old medical text warning of the 'tubercular taint' that could be passed on through risky marriage. I find out that the pale dress hanging on its stand is a Romantic era maternity dress, representing how some pregnant women with tuberculosis were forced to have abortions. It was a long time before the real cause was found. Bacteria were only seen for the first time in 1676 by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, and in 1882 the microbiologist Robert Koch proved that tuberculosis was caused by bacteria.  At the entrance to the exhibition I spy a quote from the Romantic poet, Lord Byron. ' “How pale I look! – I should like, I think, to die of a consumption –because then the women would all say, 'see that poor Byron- how interesting he looks in dying!” ' Ah, the vanity of poets. I wonder how tuberculosis could ever be thought of as 'romantic'. The disease was called 'consumption' from the 14th century because of its vampire-like effect on sufferers. It mainly eats away at the lungs, causing hacking coughs and bloody sputum, sweaty fever, the body weakening and wasting away. The statistics for tuberculosis are shocking. One third of the world's population are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium responsible for causing the disease. Of those, ten percent will develop the disease. Of those, around five percent would die of it without treatment. It is currently the second most deadly infectious disease after HIV and has killed far more people overall. While it is curable with modern antibiotics, in the right conditions extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis can evolve. So what's romantic about all of this? But I'm looking at this wrong. Nowadays, we know about tuberculosis. We know about bacteria. We have antibiotics and medical advice. We have scientists with gene sequencers and electron microscopes. But for most of our history, people did not know what caused, spread, or cured tuberculosis. Forced to live alongside this mysterious and widespread disease, unpicking its mystery with slow science, people also responded with myth, imagination, and art. After all, anyone could get tuberculosis, from famous figures to the unknown. Many Romantic Era artists like Keats had it. Perhaps Byron spoke tongue-in-cheek, since his own father died of the disease. And unlike other common diseases of the time, like smallpox, tuberculosis was less devastating on the appearance. A waifish, pale appearance was even considered fashionable, tuberculosis or not. This is not so different from today's unchanging fashions of the catwalk, or tastes for sparkly skinny vampires, then.  And while many artists had tuberculosis, could tuberculosis actually create the artist? Some people have theorised that tuberculosis enhanced creativity by inducing spes phthisica, a state of euphoric creativity before death. While it's likely that this state was only based on romantic anecdotes, perhaps a feverish delirium could inspire strange and artistic ideas. Anna showed me around the exhibition, inside the softly lit circular room of the Theatrum Anatomicum. Her artworks tell the story of how we have long tried to understand tuberculosis. “Because it's had such an impact on humanity, there are a lot of myths around tuberculosis,” Anna says. “And there's a lot of different areas of medical research that have changed over time. There's this fascinating cultural story alongside the microbiological side.”  How was it transmitted? “Where there's dust there's danger,” warns a 1902 guide by the National Society for the Prevention of Consumption. At this time, tuberculosis was thought to be spread mainly by infected spit that dried on specks of dust. Invite a few tuberculosis sufferers into your home, let them spit on the floor, neglect to sweep for a few weeks, and eventually you could be stirring up clouds of death with your broom. Close up, I see the moth-like objects on the wall are actually tiny grey lungs. These are made from felt and dust, by Anna and people who have attended her interactive workshops. The advice was almost right in that tuberculosis can be spread by sputum, sprayed into the air by coughing, but dust could not spread tuberculosis. Drying out sputum droplets tends to kill the bacterium.  Today, thanks to whole genome sequencing, transmission of a disease can be more precisely mapped. I learn about this by examining a stand holding an old 'pocket-bottle for coughers'. The Blue Henry is an attractive blue glass bottle with a silver lid, intended to provide a safe and fashionable receptacle for sufferers to cough up blood in public. Like many of the artworks on display here, Anna has combined the past and present of tuberculosis on this object. The top is engraved with a patient transmission map, produced by the research of the Modernising Medical Microbiology (MMM) project. Today, the MMM scientists investigate deadly bacterial diseases by sequencing the genomes of the bacteria responsible. Using the sequences, they can identify which strains are responsible for disease outbreaks, and they can also map the transmission of an outbreak back to its source. The diagram on the lid of the Blue Henry shows how multiple people were infected by one person, who was in turn infected by Patient Zero, the first person to get the disease. Prior to whole-genome sequencing, unravelling the spread of a disease would have relied on a laborious process of interviews and piecing together likely infection scenarios. How was tuberculosis treated? There are fascinating items showing how tuberculosis treatments were marketed. 'REST... to beat TB' one medical poster declares, showing an improbably merry man as he lies in bed, resting off his tuberculosis. Resting was supposed to help recovery by lowering the breathing rate and giving the lungs of sufferers less work to do. Patients would also be shuttled off to sanatoriums in mountainous regions, where the air was thinner and thought to be better for the body. Anna tells me about an infamous Welsh mountain sanatorium, Craig-y-nos, where children were forced to sleep outside in fresh yet painfully frosty air, since this was thought to be another benefit. A jaunty magazine poses an attractive young couple under the headline, 'I had TB!'. Below this, Anna has arranged an innocuous little microscope slide of stained M. tuberculosis from sputum, the foe in question.  But there are also works based on more sinister tools. Anna explains that artificial pneumothorax- collapsing a lung- was once a common treatment. The idea was that collapsing the lung would 'rest' it, giving the lung a break to tackle its tuberculosis infection, and also starving the tuberculosis bacteria of oxygen. Around one third of tuberculosis patients were treated to this between the 1930s to 1950s, including the writer George Orwell. It's a toe-curlingly unpleasant idea, but Anna tells me that some small, recent trials suggest this antiquated treatment might help fight the modern rise of extremely-drug resistant tuberculosis. Sometimes medicine, like history, turns in cycles.  Textiles and dyes also play a large part in the history of tuberculosis. The maternity dress has been dyed with walnut husks, madder root and safflower. All common natural dyes, and all early treatments for tuberculosis. There's a vial and fabric-stains of Prontosil, the world's first 'sulfonamide' drug which could slow the growth of bacteria. It was produced by Bayer, today known as a chemical pharmaceutical giant, but who began as a dye manufacturer. Bayer's large chemical laboratories for producing dyes were perfect playgrounds to test out new chemical combinations. With ready supplies of coal tar, a by-product of coal production, a base for many dyes, and the bane of my childhood thanks to my dad's inexplicable fondness for coal-tar soap, many scientists tried to produce dyes to specifically target bacteria. Along with other useful products like aspirin, Bayer eventually produced Prontosil, and medicines derived from this bright red substance were widely used in bandages during WWII. It also had the side effect of dyeing the skin red. Anna has also found staining effects in modern treatments for tuberculosis, and she used the growth media for Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) (an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis used as a vaccine for TB) to add striking touches of pale blue to some of her artworks.  I also find out that Byron's vain wish to be pale and interesting would get a colourful update. Anna reveals that a modern antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, rifampicin, can cause the tears and sweat to turn orange. “In a way, they look like they have a nice tan,” she commented wryly. “So it's interesting how that link between fashion, appearances and tuberculosis has come about again.” Stories and the Sublime Anna is fascinated by objects that are tainted with the story of the disease, and has added more subtle combinations of old and new stories. The dress and tiny lungs are infused with the extracted DNA of M. tuberculosis. There is no danger that the DNA can harm anybody. But the DNA's presence in objects so close to me make me feel face-to-face with the bacterium itself, laid open before me. It is an intimate and respectful meeting, one without infection, disease, or pain. “My research into this exhibition began with conversations with scientists, and reading about the disease, and the more I did the more stories I found. The strangeness of everything, the stories, it's not really what people expect,” reflected Anna. “I'm definitely planning to take the work further, I think there's many more stories to be told.” She also runs hands-on workshops to explore the history of tuberculosis further, and sometimes people attend who have experienced old tuberculosis treatments first-hand.  Looking round the exhibition, I'm struck by how much it has filled in the cultural side of tuberculosis to me, something which was entirely missing when I studied the disease at university. In modern times we might easily think that only the scientific view remains now. With sophisticated technologies or new drugs, scientists work towards understanding cause, transmission, and treatment in ever closer detail. But cultural understanding of the disease is something uniquely human. And inspiration and appreciation of the microbiological world play a vital role in pushing scientific discoveries. Anna points out that microbiology is still a relatively new science. It was only a few hundred years ago that Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a textiles dealer, first saw microbes under his homemade microscopes. Van Leeuwenhoek was not a scientist, he was a textiles dealer used to examining thread counts under magnifying glasses. Yet he was inspired to explore the microscopic world after seeing pictures from Robert Hooke's 1665 book, Micrographia, with its detailed illustrations of textiles in the microscopic world. Van Leeuwenhoek went on to make a number of groundbreaking discoveries in science, and was always guided by his interest and appreciation in what he saw. “We're at a fascinating time when new technology is available and revealing more about the microbial world,” Anna said. She is also looking forward to exploring our relationship with other infamous bacteria, including artworks based on Staphylococcus aureus, the agent responsible for MRSA.  I asked Anna what she wanted people to go away from the exhibition with a sense of. “To me bacteria have this effect of the sublime. With all the effect they've had on humanity, but the fact that they're fascinating and beautiful too. Ideally I'd like people to come away from the exhibition with a sense of the bacterial sublime, to understand the sea of bacteria they're a part of, and that they're super-organisms containing bacteria. I'd like people to understand that.”  Additional Information Anna Dumitriu explains more about her artwork and inspiration in this film. Anna Dumitriu received a Leverhulme Trust Artist in Residence Award in 2011 to work with the Modernising Medical Microbiology project led by the University of Oxford, Nuffield Centre for Clinical Medicine, in conjunction with Public Health England. 'The Romantic Disease' exhibition is funded by the Wellcome Trust. The exhibition will be shown at the Waag Society until 27th July, and the Art Laboratory in Berlin from 26th September - November 2014. Links Anna Dumitriu's website: http://normalflora.co.uk/ Modernising Medical Microbiology website: http://modmedmicro.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ Waag Society: http://waag.org/en/event/romantic-disease-exhibition Further reading

1 Comment

I am a physician scientist for TB.I was born in China but now I am working for US government living in Washington DC area.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorNot quite a blog, but things that I have written. Please note - these writings are unedited, for the purposes of flexing my fingers, and no doubt contain grammatical errors and carelessness of expression I wouldn't allow in professional writing. Categories

All

Archives

June 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed