|

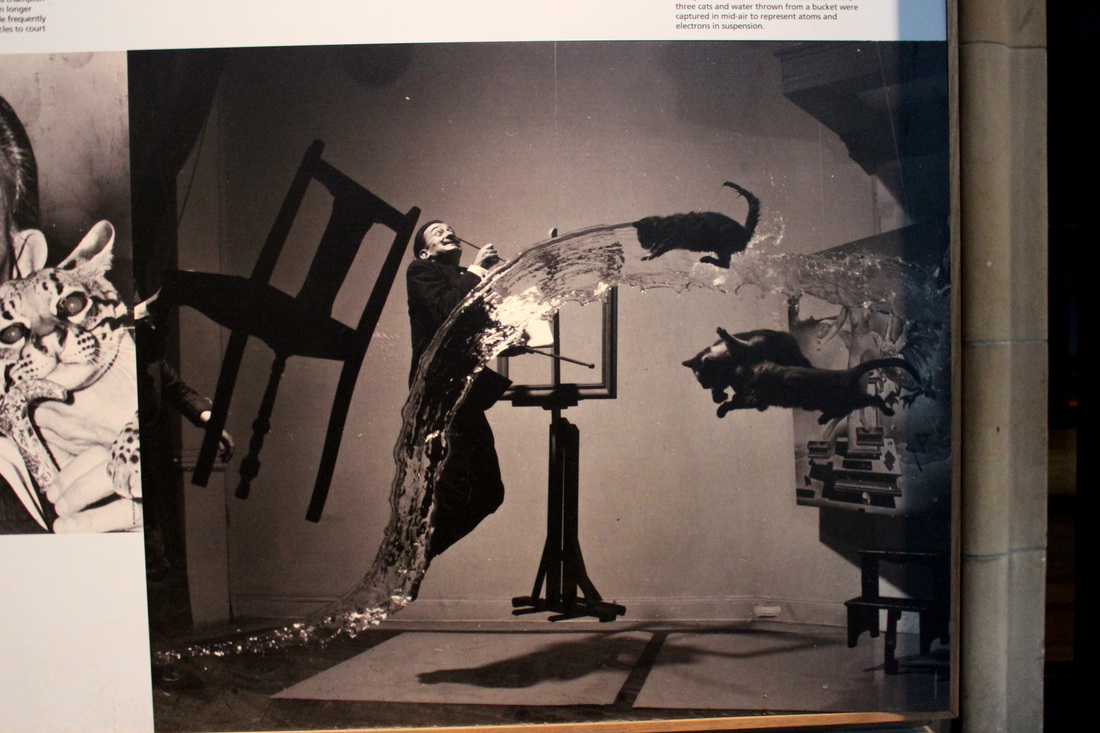

I'm learning new things about Salvador Dali. Earlier this year, I visited the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, and discovered a room full of Dali paintings which I had never seen before. When an artist is as famous and familiar, like Dali, they have assumed a public identity through their most famous and familiar paintings. The distintegration of time, the fragile stem-legged elephants haunting desolate yet colourful deserts, tigers leaping after flowing cloth. I've love the detail of Dali's Old Master-style, even and especially the way it slightly repulses me in its hyper-real depiction of unpleasant drooping textures and Surreal disturbia. I'd never seen his painting of a vision of Africa, lushly dark in black and red, showing the painter poised in the corner, drawing up his vision like a magician gesturing magic. Or his painting, 'The Great Paranoiac'. Feverish, fainting figures stumble across the canvas, reaching out weakly for support. A multitude of small bodies and stories make up the shape of Dali's own face, haunted and flickering. Looking into the painting, my eyes flicked back and forth between the different ways of seeing, the shivering figures and the great bowed head. It's a painting which personifies mental illness with ruthless clarity. So, Salvador Dali, surrealist and psychologist. But recently I found out that much more science permeates his work. At the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum hangs 'Christ of St John of the Cross'. The painting is based on a 16th century drawing by St John of the Cross, a Spanish friar. In the painting Christ is pressed against a cross, suspended in darkness over a stretch of shimmering clouds and skies, sculpted sandy horizon. Dali based his painting on two dreams he had, and built physics and mathematics into its composition. His first dream gave him an idea for the shape of the figure and perspective, based on his imagination of the nucleus of an atom. Dali had studied physics and dreamt dreams of atoms in the wake of WWII. The discovery of the atomic nature of the universe held a special meaning for him.  "In 1950 I had a cosmic dream in which I saw in colour this image, which in my dream represents the nucleus of the atom. This nucleus afterwards took on a metaphysical meaning. I consider it to be the very unity of the Universe, Christ." He used the mathematical theories of Luca Pacioli to work out the striking proportions of the painting. Outside the room holding the painting, I also spied this intriguing photograph, 'Dali Atomicus'. It displays a remarkable timing of coordinated chaos. I wonder how many cats had to be flung. After I came home and did a little searching, I found out that 'Christ of St John of the Cross' is only the tip of the iceberg. There is much, much more to find out about Dali and his inspiration borne of maths, science, and religion.

0 Comments

This is about why I went into science communication. It's also about why I studied science. And about why I feel so passionately about visual art. It's all of those things, because I think they come from the same place. On my birthday, I went to Hoge Veluwe National Park in the Netherlands. The park is a beautiful amalgamation of rough green heathland and distant tree copses, red-barked pines and savannah grasslands, African desert dunes and twisted silvered trees. I cycled through and marvelled at how the land changed as I went further in.

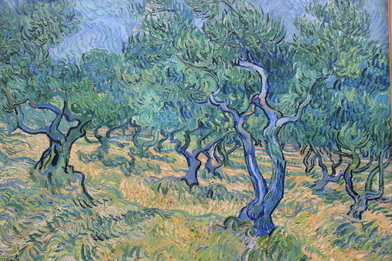

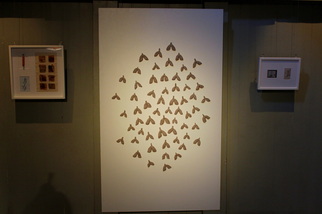

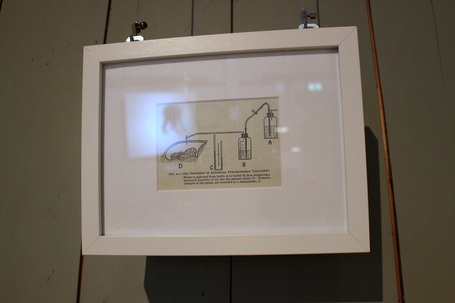

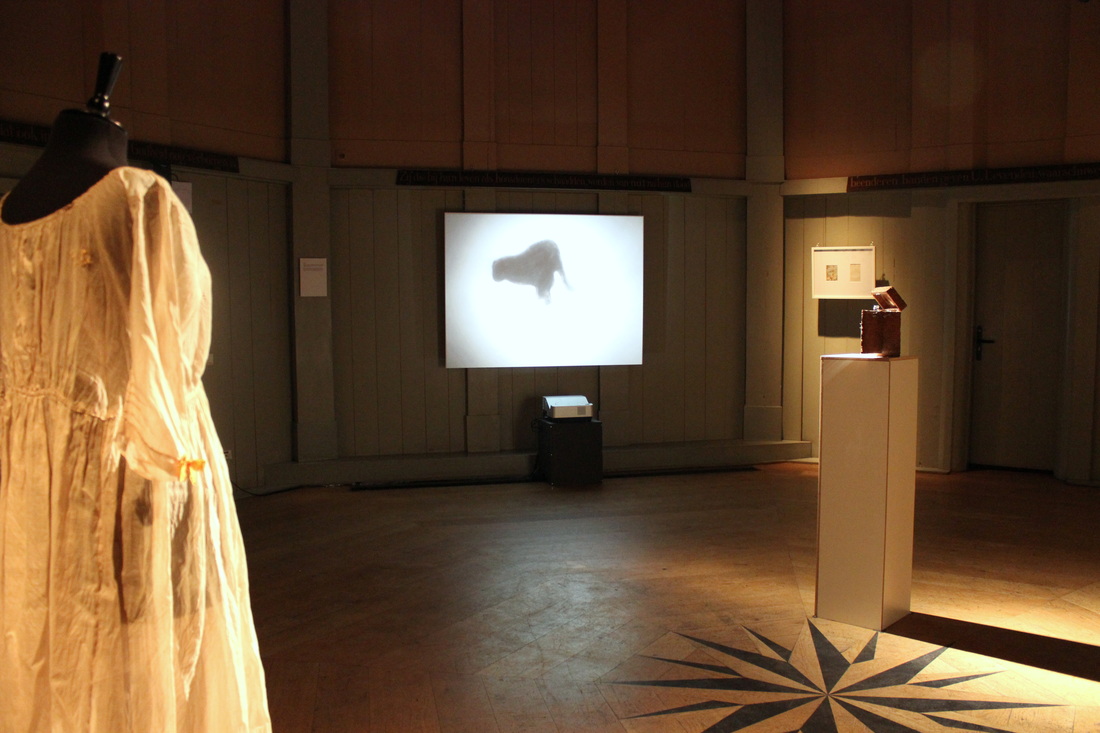

And in one wing, the van Goghs. The paintings are laid out chronologically, and feature a lot of early van Gogh. There are examples of the first still-life paintings he produced as he was first learning to use oil paint, in 1881. And several works from 1882-1885, when he was dedicated to depicting peasant life and rural farming. The museum has The Potato Eaters and Loom with Weaver. There are also a few landscapes from this period. Boggy-dark, muted green, obedient in their depiction of reality and technique. What struck me is that, if you associate van Gogh with the most famous and reprinted works that came later, these paintings are remarkably boring. Superficially attractive in their realism, with clues to his style of painting throughout. But nothing that you might not already know about these landscapes, these scenes, these ideas. The Sower, though. I went in close to count how many shades of blue. You can see the same shades hitting the canvas in strokes that might overlap, but which never blend. He didn't smear the colours together, he laid them on. There's a layer of grey-blue strokes, a layer of pale blue strokes, a layer of purplish-lilac-blue strokes. Spattered throughout, shrill dabs of orange. Orange and blue are opposites and so in terms of seeing colour, the contrast can't be greater. And when I stepped back... everything changed. It was then I realised there's an ideal viewing distance for van Gogh's most colourful paintings. It's the point where contrast between blues and orange and yellow start working together. They sink into the eyes. And the effect is like music. Every paintstroke a beat, a note, a particular sound. Taken all together, the contrasts of colour work like a symphony. And in this painting, against everything playing out of the foreground, in the background the linear motion of the sun rays blaze outwards and set a constant tempo. Close up you see the notes, but from further away you can see the full music. And this. Far more beautiful than his titular Sunflowers, that yellowish sunny painting I was first introduced to in primary school. This is Four Sunflowers Gone to Seed. Again, close up I saw the strokes. Stepping away, I saw how everything came together to make four dying flowerheads come ablaze. Contrast. That's why I like Vincent van Gogh's style, his paintings. I have been thinking a lot about the Sublime, since interviewing Anna Dumitriu about her artwork. If we take the Sublime to mean an incredible beauty, it's something that can only be sharpened and highlighted by contrast. Orange against blue, black against white, paint contrasts etched onto canvas, a symphony of something beautiful that van Gogh saw. The painting was full of movement and direction and tempo.  Even van Gogh's life was about contrast. Beauty and darkness, depression and mania. He could see incredible visions of the Sublime in the scenes he painted, of the countryside, of objects, of people, of streets. He painted his excitement and fervour into his works, striking out each piece into a moving orchestra of colours and brushstrokes and direction and tempo and blackness. Then there were the times of horror, of nothingness, melancholia. Perhaps the Sublime comes and goes. Like the sun, you can't stare at it forever. In between the beauty, the ordinariness, and beyond that, the complete lack of beauty.  I studied van Gogh in high school. The first time I saw an exhibition of his work was as a visiting exhibition at a modern art museum in Seoul, South Korea. What struck me then was the shininess of the colourful paint, which looked almost freshly applied. The chapped texture of the brushstrokes buttering the colours on. They were famous, and old, and alive. And I'd had no idea he had created so many paintings. Like most people, I grew up on a diet of Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers. The same image turned out and appearing in textbooks, posters, school lesson photocopies, again and again, as though on a carousel.  Colour has always been what I like best in paintings. Colour and contrast. Colour played against blackness to bring it out and make it breathe. Sitting in the museum, staring into a van Gogh painting, I felt an odd feeling, like a brief psychological disjunction. I was reading a message written out in paintstrokes and paintings by another long-passed artist's work. Did I feel as he had felt? Did he know what it was that he created in his work?  Feeling how another person feels, seeing how they see. I thought about this a lot as the museum closed and I started pedalling back through the park. Along with visual art, I have always liked science. I like to know the names of things, and why things happen. I like to see in closer and closer detail how something works, from learning about a leaf, to the cell, to the mitochondrion inside and beyond to where you can no longer see, in the diagrammatic sketching of the visualised electron transport chain. School had always been about progressing in greater and greater levels, so it's not entirely unsurprising that I studied Biology at university. Knowing these things gives me a sense of similar excitement to looking at a beautiful contrast of colours in a painting. And to step back from the details, to try and hold everything in your head at the same time as you look at the bigger picture- how the machinery of the genes moves the molecules that connect up the proteins that altogether animate the entire organism... it's bewildering, and it's incredibly difficult. That's science. But it seemed to me that trying to hold everything together like that is not so different from stepping back from a van Gogh, and finding the point where everything begins to move and work together as one. And that was why I'd become interested in science communication, too. Science communication can have many roles and they are best explored in another article. I'll define two major types of science communication here, though. One reason is to communicate clearly, to rearrange a piece of complex jargon-filled research into something legible to a non-specialist. The second reason is to make you feel as I feel. There's a beauty in science communication, because it is an art form. The way an idea is expressed, whether through words, a picture, a book, a sentence, an article, a concept. If I could create something that communicates that flash of beauty, fascination, of that Sublime in science, then I will have shared what I see in it. And that's the true point of science communication and science engagement to me. If I ever achieve that then it will mean, like van Gogh to his viewers, that I succeeded. What is the romantic disease? Watch the film below to see artist Anna Dumitriu talking about her exhibition. Anna Dumitriu explains the stories behind her exhibition here I’m in a room with humanity's biggest killer. It began eating away at us over 9000 years ago, and has never really stopped. The marks of our relationship surround me in an array of medical leaflets and dyed fabrics. Mysterious objects sit on stands. A glistening set of metal needles and devices inside a spongy wooden case. There's a tiny, bare bed, and a ghostly pale dress. A collection of tiny felted grey lungs that resemble a group of settled moths on a wall. This is an exhibition on tuberculosis. 'The Romantic Disease' has been created by Anna Dumitriu, a British artist with a taste for microbiology and emerging technologies. She is the artist-in-residence for the Modernising Medical Microbiology project, a collaboration between Oxford University and Public Health England, and she was inspired to create this exhibition by their research into bacterial diseases. The exhibition is on tour through Europe, and is currently hosted in the Theatrum Anatomicum at Waag Society in Amsterdam.  What caused tuberculosis? On one side of the room I see an animated black dog circling and pacing endlessly. It represents one early interpretation, the 'demon dog'. This dog would enter the bodies of sufferers and bark, making them cough. Later, people thought tuberculosis could be inherited. On another wall I read an old medical text warning of the 'tubercular taint' that could be passed on through risky marriage. I find out that the pale dress hanging on its stand is a Romantic era maternity dress, representing how some pregnant women with tuberculosis were forced to have abortions. It was a long time before the real cause was found. Bacteria were only seen for the first time in 1676 by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, and in 1882 the microbiologist Robert Koch proved that tuberculosis was caused by bacteria.  At the entrance to the exhibition I spy a quote from the Romantic poet, Lord Byron. ' “How pale I look! – I should like, I think, to die of a consumption –because then the women would all say, 'see that poor Byron- how interesting he looks in dying!” ' Ah, the vanity of poets. I wonder how tuberculosis could ever be thought of as 'romantic'. The disease was called 'consumption' from the 14th century because of its vampire-like effect on sufferers. It mainly eats away at the lungs, causing hacking coughs and bloody sputum, sweaty fever, the body weakening and wasting away. The statistics for tuberculosis are shocking. One third of the world's population are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium responsible for causing the disease. Of those, ten percent will develop the disease. Of those, around five percent would die of it without treatment. It is currently the second most deadly infectious disease after HIV and has killed far more people overall. While it is curable with modern antibiotics, in the right conditions extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis can evolve. So what's romantic about all of this? But I'm looking at this wrong. Nowadays, we know about tuberculosis. We know about bacteria. We have antibiotics and medical advice. We have scientists with gene sequencers and electron microscopes. But for most of our history, people did not know what caused, spread, or cured tuberculosis. Forced to live alongside this mysterious and widespread disease, unpicking its mystery with slow science, people also responded with myth, imagination, and art. After all, anyone could get tuberculosis, from famous figures to the unknown. Many Romantic Era artists like Keats had it. Perhaps Byron spoke tongue-in-cheek, since his own father died of the disease. And unlike other common diseases of the time, like smallpox, tuberculosis was less devastating on the appearance. A waifish, pale appearance was even considered fashionable, tuberculosis or not. This is not so different from today's unchanging fashions of the catwalk, or tastes for sparkly skinny vampires, then.  And while many artists had tuberculosis, could tuberculosis actually create the artist? Some people have theorised that tuberculosis enhanced creativity by inducing spes phthisica, a state of euphoric creativity before death. While it's likely that this state was only based on romantic anecdotes, perhaps a feverish delirium could inspire strange and artistic ideas. Anna showed me around the exhibition, inside the softly lit circular room of the Theatrum Anatomicum. Her artworks tell the story of how we have long tried to understand tuberculosis. “Because it's had such an impact on humanity, there are a lot of myths around tuberculosis,” Anna says. “And there's a lot of different areas of medical research that have changed over time. There's this fascinating cultural story alongside the microbiological side.”  How was it transmitted? “Where there's dust there's danger,” warns a 1902 guide by the National Society for the Prevention of Consumption. At this time, tuberculosis was thought to be spread mainly by infected spit that dried on specks of dust. Invite a few tuberculosis sufferers into your home, let them spit on the floor, neglect to sweep for a few weeks, and eventually you could be stirring up clouds of death with your broom. Close up, I see the moth-like objects on the wall are actually tiny grey lungs. These are made from felt and dust, by Anna and people who have attended her interactive workshops. The advice was almost right in that tuberculosis can be spread by sputum, sprayed into the air by coughing, but dust could not spread tuberculosis. Drying out sputum droplets tends to kill the bacterium.  Today, thanks to whole genome sequencing, transmission of a disease can be more precisely mapped. I learn about this by examining a stand holding an old 'pocket-bottle for coughers'. The Blue Henry is an attractive blue glass bottle with a silver lid, intended to provide a safe and fashionable receptacle for sufferers to cough up blood in public. Like many of the artworks on display here, Anna has combined the past and present of tuberculosis on this object. The top is engraved with a patient transmission map, produced by the research of the Modernising Medical Microbiology (MMM) project. Today, the MMM scientists investigate deadly bacterial diseases by sequencing the genomes of the bacteria responsible. Using the sequences, they can identify which strains are responsible for disease outbreaks, and they can also map the transmission of an outbreak back to its source. The diagram on the lid of the Blue Henry shows how multiple people were infected by one person, who was in turn infected by Patient Zero, the first person to get the disease. Prior to whole-genome sequencing, unravelling the spread of a disease would have relied on a laborious process of interviews and piecing together likely infection scenarios. How was tuberculosis treated? There are fascinating items showing how tuberculosis treatments were marketed. 'REST... to beat TB' one medical poster declares, showing an improbably merry man as he lies in bed, resting off his tuberculosis. Resting was supposed to help recovery by lowering the breathing rate and giving the lungs of sufferers less work to do. Patients would also be shuttled off to sanatoriums in mountainous regions, where the air was thinner and thought to be better for the body. Anna tells me about an infamous Welsh mountain sanatorium, Craig-y-nos, where children were forced to sleep outside in fresh yet painfully frosty air, since this was thought to be another benefit. A jaunty magazine poses an attractive young couple under the headline, 'I had TB!'. Below this, Anna has arranged an innocuous little microscope slide of stained M. tuberculosis from sputum, the foe in question.  But there are also works based on more sinister tools. Anna explains that artificial pneumothorax- collapsing a lung- was once a common treatment. The idea was that collapsing the lung would 'rest' it, giving the lung a break to tackle its tuberculosis infection, and also starving the tuberculosis bacteria of oxygen. Around one third of tuberculosis patients were treated to this between the 1930s to 1950s, including the writer George Orwell. It's a toe-curlingly unpleasant idea, but Anna tells me that some small, recent trials suggest this antiquated treatment might help fight the modern rise of extremely-drug resistant tuberculosis. Sometimes medicine, like history, turns in cycles.  Textiles and dyes also play a large part in the history of tuberculosis. The maternity dress has been dyed with walnut husks, madder root and safflower. All common natural dyes, and all early treatments for tuberculosis. There's a vial and fabric-stains of Prontosil, the world's first 'sulfonamide' drug which could slow the growth of bacteria. It was produced by Bayer, today known as a chemical pharmaceutical giant, but who began as a dye manufacturer. Bayer's large chemical laboratories for producing dyes were perfect playgrounds to test out new chemical combinations. With ready supplies of coal tar, a by-product of coal production, a base for many dyes, and the bane of my childhood thanks to my dad's inexplicable fondness for coal-tar soap, many scientists tried to produce dyes to specifically target bacteria. Along with other useful products like aspirin, Bayer eventually produced Prontosil, and medicines derived from this bright red substance were widely used in bandages during WWII. It also had the side effect of dyeing the skin red. Anna has also found staining effects in modern treatments for tuberculosis, and she used the growth media for Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) (an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis used as a vaccine for TB) to add striking touches of pale blue to some of her artworks.  I also find out that Byron's vain wish to be pale and interesting would get a colourful update. Anna reveals that a modern antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, rifampicin, can cause the tears and sweat to turn orange. “In a way, they look like they have a nice tan,” she commented wryly. “So it's interesting how that link between fashion, appearances and tuberculosis has come about again.” Stories and the Sublime Anna is fascinated by objects that are tainted with the story of the disease, and has added more subtle combinations of old and new stories. The dress and tiny lungs are infused with the extracted DNA of M. tuberculosis. There is no danger that the DNA can harm anybody. But the DNA's presence in objects so close to me make me feel face-to-face with the bacterium itself, laid open before me. It is an intimate and respectful meeting, one without infection, disease, or pain. “My research into this exhibition began with conversations with scientists, and reading about the disease, and the more I did the more stories I found. The strangeness of everything, the stories, it's not really what people expect,” reflected Anna. “I'm definitely planning to take the work further, I think there's many more stories to be told.” She also runs hands-on workshops to explore the history of tuberculosis further, and sometimes people attend who have experienced old tuberculosis treatments first-hand.  Looking round the exhibition, I'm struck by how much it has filled in the cultural side of tuberculosis to me, something which was entirely missing when I studied the disease at university. In modern times we might easily think that only the scientific view remains now. With sophisticated technologies or new drugs, scientists work towards understanding cause, transmission, and treatment in ever closer detail. But cultural understanding of the disease is something uniquely human. And inspiration and appreciation of the microbiological world play a vital role in pushing scientific discoveries. Anna points out that microbiology is still a relatively new science. It was only a few hundred years ago that Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a textiles dealer, first saw microbes under his homemade microscopes. Van Leeuwenhoek was not a scientist, he was a textiles dealer used to examining thread counts under magnifying glasses. Yet he was inspired to explore the microscopic world after seeing pictures from Robert Hooke's 1665 book, Micrographia, with its detailed illustrations of textiles in the microscopic world. Van Leeuwenhoek went on to make a number of groundbreaking discoveries in science, and was always guided by his interest and appreciation in what he saw. “We're at a fascinating time when new technology is available and revealing more about the microbial world,” Anna said. She is also looking forward to exploring our relationship with other infamous bacteria, including artworks based on Staphylococcus aureus, the agent responsible for MRSA.  I asked Anna what she wanted people to go away from the exhibition with a sense of. “To me bacteria have this effect of the sublime. With all the effect they've had on humanity, but the fact that they're fascinating and beautiful too. Ideally I'd like people to come away from the exhibition with a sense of the bacterial sublime, to understand the sea of bacteria they're a part of, and that they're super-organisms containing bacteria. I'd like people to understand that.”  Additional Information Anna Dumitriu explains more about her artwork and inspiration in this film. Anna Dumitriu received a Leverhulme Trust Artist in Residence Award in 2011 to work with the Modernising Medical Microbiology project led by the University of Oxford, Nuffield Centre for Clinical Medicine, in conjunction with Public Health England. 'The Romantic Disease' exhibition is funded by the Wellcome Trust. The exhibition will be shown at the Waag Society until 27th July, and the Art Laboratory in Berlin from 26th September - November 2014. Links Anna Dumitriu's website: http://normalflora.co.uk/ Modernising Medical Microbiology website: http://modmedmicro.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ Waag Society: http://waag.org/en/event/romantic-disease-exhibition Further reading

|

AuthorNot quite a blog, but things that I have written. Please note - these writings are unedited, for the purposes of flexing my fingers, and no doubt contain grammatical errors and carelessness of expression I wouldn't allow in professional writing. Categories

All

Archives

June 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed