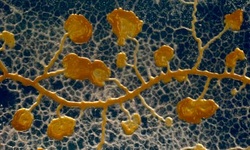

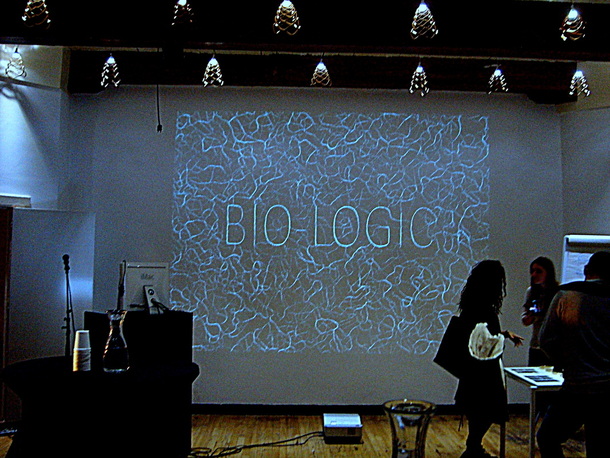

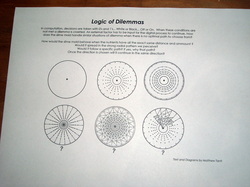

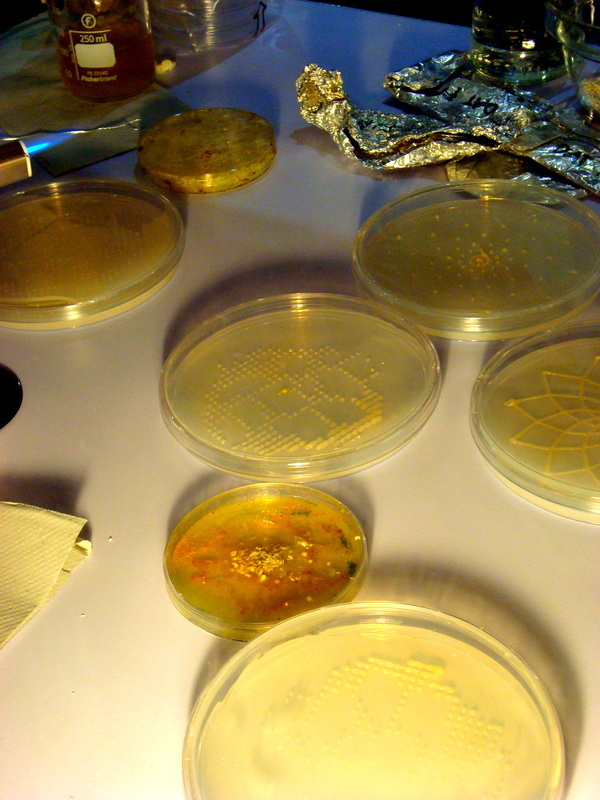

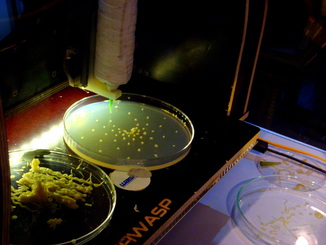

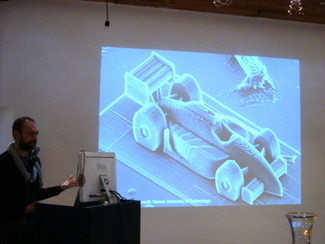

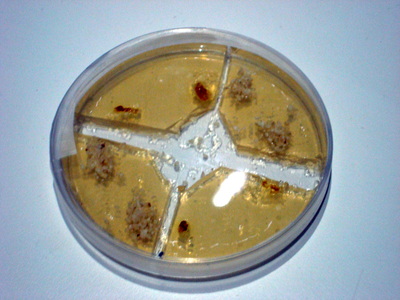

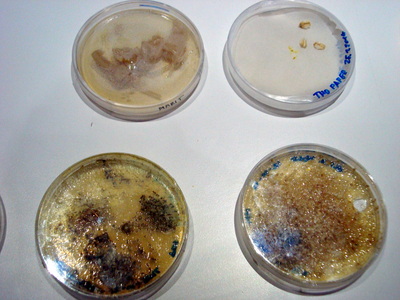

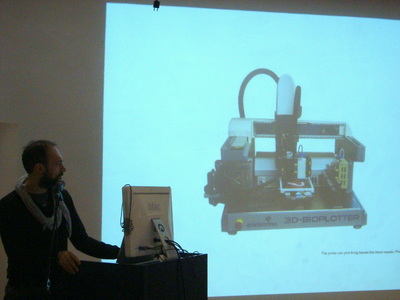

I like slime moulds, and so should you. Let me convince you. Slime moulds seem to bridge the gap between fungi and animals. In a nutshell, they are a glistening goop that spreads and develops in a webbed network of frilly fingers. But this is an intelligent goop. Slime moulds respond malleably to their environment. They can work out the most efficient shape to morph into in order to reach multiple food sources. Scientists have shown this ability compares favourably to some of the most efficiently planned human transport systems. When times are hard, the slimes can change form to produce fruiting spores, sending its spores away to find better lands. When two slime moulds of the same species meet, they join forces into one large super-slime. Best of all, they seem pleasantly benevolent compared to many other microorganisms. No slime mould has yet proved itself to be a human pathogen. And they not only eat bacteria, they farm it. So slime moulds are a wonderful piece of the biodiversity puzzle around us. And we're slowly getting to know more about them. They have cropped up in the 2010 Ig Nobels, for instance. But there are some incredible combinations of man-made technology meeting nature, like fabulously weird experiments using slime moulds as living computing interfaces (quick translation: cyborg technology). Andrew Adamatzky's group at the University of West of England have almost given slime moulds a human face. And on 27th January 2013, I attended an exhibition of slime moulds and 3D printing. It was an interdisciplinary event hosted by the Waag Society, an arts-meets-sciences-meets-design sort of incident. While the supposed schism of the arts and sciences has long been debated and reinvented to zombified death, introducing 'design' as part of interdisciplinary events has crept in on the tides of 21st century technology. The exhibition showcased the results of a two-day workshop where participants designed with slime moulds and 3D printers. This was to be my first visit to the Waag Society, institute for art, science and technology, and I'll admit, I was wary. I hardly knew much about 3D printing on a small-scale, and how could you design with a living organism? To prepare myself for disappointment, my pessimistic mind conjured up images of an exhibition space containing conceptual sculptures splashed 'artistically' with slime mould goop. There might be a lot of dainty talk using inaccessible artspeak. In short it could be all show, no engagement. But there was no need for these pessimistic thoughts. There was plenty of show and plenty of engagement. The beautiful old Waag building is an excellent space for science-related public events. The winding staircase, curved walls and old architecture-style is fertile ground for imagining classical scientists pursuing their work. For the Romantics, where else should you be bringing new creations to life, other than at the top of a wood-panelled, historical tower? Indeed Rembrandt immortalised dissections carried out in the Waag. Inside there was a healthy mix of public, scientists, and designers. A few small tables showed the results of the two-day Bio-Logic workshop. A table held a couple of stewpots serving as simple incubators, and another held an array of petridishes containing yellowish agar and seeded with slime mould spores. A few computers with coding programs. A 3D printer in a modified box which served as a sterile cabinet.

Afterwards, scientists, designers and public mingled to discuss ideas and ask questions. I loved thinking of the little flake of slime mould spore material in their dormant state. Ostensibly dry and dead to the eye, but merely waiting. Sensing their surroundings. Unfurling, slowly, responding. Molecular mechanisms begin to cascade, moisture is drawn up. The machinery unfolds. The mould becomes a mobile slime again and reaches for food. I learned more about the slime mould being used, Physarum polycephalum. It can move as quickly as one centimetre an hour. The giant cells it forms are called plasmodia, and contain several nuclei. As in any microbiology lab, contamination is an ever-present problem and can ruin carefully constructed petridishes, but sometimes slime moulds have used the invading growths of fungi as a scaffolding to climb out of the petridish. The moulds can also lay down a trail of physical 'memory'. They can leave crystals behind as chemical signals, marking where they have explored. They can also keep time. When researchers exposed a slime mould to a pattern of regular temperature changes, it learned to anticipate these environmental changes. One visitor asked if the slime moulds could be used to make a 'circuit switch'. And the scientist's answer? Yes! See here for more information. A hacked 3D printer designs structures out of organic material, and the slime moulds redefine these structures. It's a start of a design exploration, bringing together technology and living matter.

So what do these slime moulds look like in action? You can watch a beautiful time-lapse video here.

3 Comments

This is about why I went into science communication. It's also about why I studied science. And about why I feel so passionately about visual art. It's all of those things, because I think they come from the same place. On my birthday, I went to Hoge Veluwe National Park in the Netherlands. The park is a beautiful amalgamation of rough green heathland and distant tree copses, red-barked pines and savannah grasslands, African desert dunes and twisted silvered trees. I cycled through and marvelled at how the land changed as I went further in.

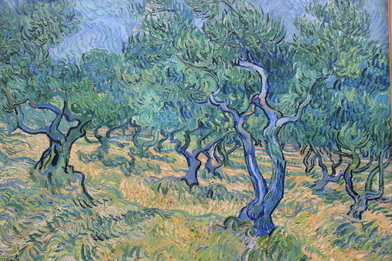

And in one wing, the van Goghs. The paintings are laid out chronologically, and feature a lot of early van Gogh. There are examples of the first still-life paintings he produced as he was first learning to use oil paint, in 1881. And several works from 1882-1885, when he was dedicated to depicting peasant life and rural farming. The museum has The Potato Eaters and Loom with Weaver. There are also a few landscapes from this period. Boggy-dark, muted green, obedient in their depiction of reality and technique. What struck me is that, if you associate van Gogh with the most famous and reprinted works that came later, these paintings are remarkably boring. Superficially attractive in their realism, with clues to his style of painting throughout. But nothing that you might not already know about these landscapes, these scenes, these ideas. The Sower, though. I went in close to count how many shades of blue. You can see the same shades hitting the canvas in strokes that might overlap, but which never blend. He didn't smear the colours together, he laid them on. There's a layer of grey-blue strokes, a layer of pale blue strokes, a layer of purplish-lilac-blue strokes. Spattered throughout, shrill dabs of orange. Orange and blue are opposites and so in terms of seeing colour, the contrast can't be greater. And when I stepped back... everything changed. It was then I realised there's an ideal viewing distance for van Gogh's most colourful paintings. It's the point where contrast between blues and orange and yellow start working together. They sink into the eyes. And the effect is like music. Every paintstroke a beat, a note, a particular sound. Taken all together, the contrasts of colour work like a symphony. And in this painting, against everything playing out of the foreground, in the background the linear motion of the sun rays blaze outwards and set a constant tempo. Close up you see the notes, but from further away you can see the full music. And this. Far more beautiful than his titular Sunflowers, that yellowish sunny painting I was first introduced to in primary school. This is Four Sunflowers Gone to Seed. Again, close up I saw the strokes. Stepping away, I saw how everything came together to make four dying flowerheads come ablaze. Contrast. That's why I like Vincent van Gogh's style, his paintings. I have been thinking a lot about the Sublime, since interviewing Anna Dumitriu about her artwork. If we take the Sublime to mean an incredible beauty, it's something that can only be sharpened and highlighted by contrast. Orange against blue, black against white, paint contrasts etched onto canvas, a symphony of something beautiful that van Gogh saw. The painting was full of movement and direction and tempo.  Even van Gogh's life was about contrast. Beauty and darkness, depression and mania. He could see incredible visions of the Sublime in the scenes he painted, of the countryside, of objects, of people, of streets. He painted his excitement and fervour into his works, striking out each piece into a moving orchestra of colours and brushstrokes and direction and tempo and blackness. Then there were the times of horror, of nothingness, melancholia. Perhaps the Sublime comes and goes. Like the sun, you can't stare at it forever. In between the beauty, the ordinariness, and beyond that, the complete lack of beauty.  I studied van Gogh in high school. The first time I saw an exhibition of his work was as a visiting exhibition at a modern art museum in Seoul, South Korea. What struck me then was the shininess of the colourful paint, which looked almost freshly applied. The chapped texture of the brushstrokes buttering the colours on. They were famous, and old, and alive. And I'd had no idea he had created so many paintings. Like most people, I grew up on a diet of Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers. The same image turned out and appearing in textbooks, posters, school lesson photocopies, again and again, as though on a carousel.  Colour has always been what I like best in paintings. Colour and contrast. Colour played against blackness to bring it out and make it breathe. Sitting in the museum, staring into a van Gogh painting, I felt an odd feeling, like a brief psychological disjunction. I was reading a message written out in paintstrokes and paintings by another long-passed artist's work. Did I feel as he had felt? Did he know what it was that he created in his work?  Feeling how another person feels, seeing how they see. I thought about this a lot as the museum closed and I started pedalling back through the park. Along with visual art, I have always liked science. I like to know the names of things, and why things happen. I like to see in closer and closer detail how something works, from learning about a leaf, to the cell, to the mitochondrion inside and beyond to where you can no longer see, in the diagrammatic sketching of the visualised electron transport chain. School had always been about progressing in greater and greater levels, so it's not entirely unsurprising that I studied Biology at university. Knowing these things gives me a sense of similar excitement to looking at a beautiful contrast of colours in a painting. And to step back from the details, to try and hold everything in your head at the same time as you look at the bigger picture- how the machinery of the genes moves the molecules that connect up the proteins that altogether animate the entire organism... it's bewildering, and it's incredibly difficult. That's science. But it seemed to me that trying to hold everything together like that is not so different from stepping back from a van Gogh, and finding the point where everything begins to move and work together as one. And that was why I'd become interested in science communication, too. Science communication can have many roles and they are best explored in another article. I'll define two major types of science communication here, though. One reason is to communicate clearly, to rearrange a piece of complex jargon-filled research into something legible to a non-specialist. The second reason is to make you feel as I feel. There's a beauty in science communication, because it is an art form. The way an idea is expressed, whether through words, a picture, a book, a sentence, an article, a concept. If I could create something that communicates that flash of beauty, fascination, of that Sublime in science, then I will have shared what I see in it. And that's the true point of science communication and science engagement to me. If I ever achieve that then it will mean, like van Gogh to his viewers, that I succeeded. “Art is science made clear.”

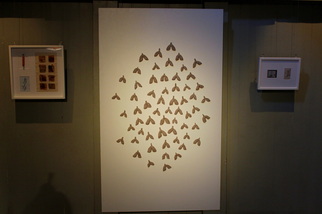

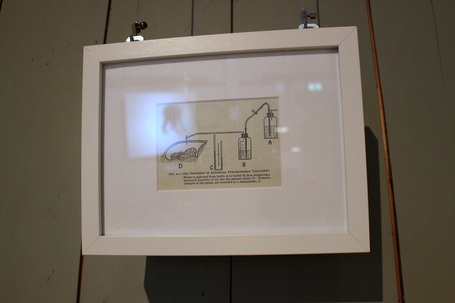

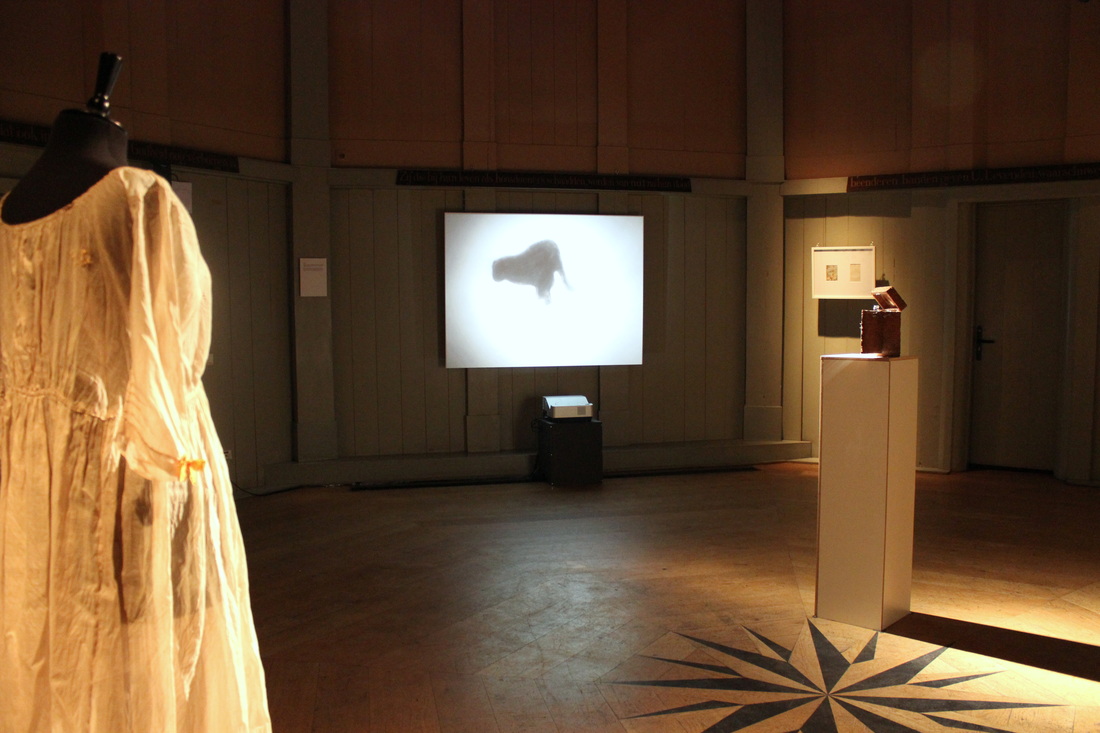

Jean Cocteau - French poet, artist and director Recently I read Imagining Science: Art, Science, and Social Change. The essays discuss a few different themes. There's an essay arguing that art is a valuable tool for anticipating scientific breakthroughs, and opening up dialogue. Some examples include the US President's Council of Advisors prepping themselves for a debate on nanotechnology, by reading Michael Crichton's Prey. Members of Congress also referred to Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale when discussing reproductive technologies. One might argue their choices of dystopian fiction to open up a reasonable debate on science. While it is a useful thing that imagination can precede scientific discovery, the most exciting stories tend to dwell on the worst possible consequences. Still, that's another point of how art can go where science can't, setting the boundaries for debate by depicting extreme outcomes. A lot of the essays in the book were also obsessed with discussing the differences between 'art' and 'science'. Most of these also seemed to be written by scientists, or sociologists, rarely self-declared artists. And a basic problem was very obvious. When you begin by laying out your definitions of what makes art 'art' and science 'science', the discussion is already lost. It becomes a debate. Art has this quality, which science does not. Science has this quality, which art does not. In struggling to define the qualities of two incredibly complex and varied fields, stereotypes appear and art is painted as mysterious, cultural and dramatic, while science is distilled into methodical, purposeful and clinical. A yawning gulf of difference opens up between the two and the writer has created C.P. Snow's two cultures anew. One writer described his experience in a particle physics laboratory. "Nobody in the lab made any reference to "beauty" in the construction of an experiment. Nobody mentioned how "feelings" shaped their work." He compared this unfavourably to his wife the painter, and the emotional reactions of people viewing her paintings, and declared an inherent and fundamental opposition in art and science. "Given all this, what I find quite amazing is the notion that artists and scientists would have much to say to one another in any realm." Another writer also emphasised a mutual exclusion of science and art. "Science is a system" whereas "Art has no agreed upon definition... It admits the possibility of nearly anything." Collaborations of art and science are "more expressive of a desire than logical possibility" and art cannot engage science, it can only engage the ethics of science. (Art, Science and Aesthetic Ethics). After a few essays like this, a person could be forgiven for thinking of science as a land of ice-hearted joyless automatons obsessively reducing the world into finer and finer slices of truth with high-powered technology, while art is a land of empathic flighty navel-gazers whose rocking hammocks are gently powered by the joie de vivre bursting from their indefinable hearts. So what do I think? I think it is all relative. To begin with, to be able to write about art and science, you must have some concept of what kind of art and what kind of science you are addressing. Do you have products of art in mind, exhibitions, theatre, paintings? Or are you thinking of the theory of art? Art defined as inspiration? Science meaning factual knowledge? The scientific method? There's never going to be much definitive progress on discussing art and science without first defining what it is you mean by art and science. Even essays that ostensibly hold similar viewpoints in the book may not, because they start off with different pieces of the concepts in mind. Now for myself, I generally take art to mean a sensation, a feeling. I am unashamedly going off my own personal experience here. To create something with your own hands. To look at a blank canvas and start transferring an internal mental vision onto the expanse of nothing. To hear a piece of music and be struck by a rush of feelings, of inspiration, a sense that something has been invented in your head which was not there before. I suppose some might call my definition of art creativity, but I think creativity describes rather the process, while art is the way of seeing, feeling, and thinking. To strip it down further, I could suggest it's about seeing beauty. And of course beauty is subjective, but I've already written about seeing the Sublime in Van Gogh's paintings, and how I found the sensation to be the same as when I learned science. I can't be the only one. Those particle physicists in the laboratory are not automatons, they would have gone into science because they saw something beautiful in it. Everybody is a scientist and an artist. Perhaps it is only less obvious because the skills used to capture art are more obvious in some forms than others. Van Leeuwenhoek made his microscopes and selected objects to study with them quite randomly. He was motivated by a love of what he saw. He used his drawing ability to express his love of what he saw. The father of the neuron, Ramon y Cabal, also saw the art in the brain cells he examined. He also happened to be interested in photography and painting. His photographs and drawings express his interest...(etc). The Origin of Species is elegantly written using that artistic medium, writing. Part of the reason that the Selfish Gene has generated such furore is because the scientific concepts within have been so clearly expressed. I don't like to set up these two concepts like two sides of a chessboard. On one side, we have Science. The other, we have Art. Media loves this false dichotomy for the easy reactions it invokes. But there's such a basic problem from the start in setting up two different items as discussion points. The instinct is to define each one by their uniqueness, and their difference from the other. Set them at odds. Make sure no progress is ever made. What is the romantic disease? Watch the film below to see artist Anna Dumitriu talking about her exhibition. Anna Dumitriu explains the stories behind her exhibition here I’m in a room with humanity's biggest killer. It began eating away at us over 9000 years ago, and has never really stopped. The marks of our relationship surround me in an array of medical leaflets and dyed fabrics. Mysterious objects sit on stands. A glistening set of metal needles and devices inside a spongy wooden case. There's a tiny, bare bed, and a ghostly pale dress. A collection of tiny felted grey lungs that resemble a group of settled moths on a wall. This is an exhibition on tuberculosis. 'The Romantic Disease' has been created by Anna Dumitriu, a British artist with a taste for microbiology and emerging technologies. She is the artist-in-residence for the Modernising Medical Microbiology project, a collaboration between Oxford University and Public Health England, and she was inspired to create this exhibition by their research into bacterial diseases. The exhibition is on tour through Europe, and is currently hosted in the Theatrum Anatomicum at Waag Society in Amsterdam.  What caused tuberculosis? On one side of the room I see an animated black dog circling and pacing endlessly. It represents one early interpretation, the 'demon dog'. This dog would enter the bodies of sufferers and bark, making them cough. Later, people thought tuberculosis could be inherited. On another wall I read an old medical text warning of the 'tubercular taint' that could be passed on through risky marriage. I find out that the pale dress hanging on its stand is a Romantic era maternity dress, representing how some pregnant women with tuberculosis were forced to have abortions. It was a long time before the real cause was found. Bacteria were only seen for the first time in 1676 by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, and in 1882 the microbiologist Robert Koch proved that tuberculosis was caused by bacteria.  At the entrance to the exhibition I spy a quote from the Romantic poet, Lord Byron. ' “How pale I look! – I should like, I think, to die of a consumption –because then the women would all say, 'see that poor Byron- how interesting he looks in dying!” ' Ah, the vanity of poets. I wonder how tuberculosis could ever be thought of as 'romantic'. The disease was called 'consumption' from the 14th century because of its vampire-like effect on sufferers. It mainly eats away at the lungs, causing hacking coughs and bloody sputum, sweaty fever, the body weakening and wasting away. The statistics for tuberculosis are shocking. One third of the world's population are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium responsible for causing the disease. Of those, ten percent will develop the disease. Of those, around five percent would die of it without treatment. It is currently the second most deadly infectious disease after HIV and has killed far more people overall. While it is curable with modern antibiotics, in the right conditions extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis can evolve. So what's romantic about all of this? But I'm looking at this wrong. Nowadays, we know about tuberculosis. We know about bacteria. We have antibiotics and medical advice. We have scientists with gene sequencers and electron microscopes. But for most of our history, people did not know what caused, spread, or cured tuberculosis. Forced to live alongside this mysterious and widespread disease, unpicking its mystery with slow science, people also responded with myth, imagination, and art. After all, anyone could get tuberculosis, from famous figures to the unknown. Many Romantic Era artists like Keats had it. Perhaps Byron spoke tongue-in-cheek, since his own father died of the disease. And unlike other common diseases of the time, like smallpox, tuberculosis was less devastating on the appearance. A waifish, pale appearance was even considered fashionable, tuberculosis or not. This is not so different from today's unchanging fashions of the catwalk, or tastes for sparkly skinny vampires, then.  And while many artists had tuberculosis, could tuberculosis actually create the artist? Some people have theorised that tuberculosis enhanced creativity by inducing spes phthisica, a state of euphoric creativity before death. While it's likely that this state was only based on romantic anecdotes, perhaps a feverish delirium could inspire strange and artistic ideas. Anna showed me around the exhibition, inside the softly lit circular room of the Theatrum Anatomicum. Her artworks tell the story of how we have long tried to understand tuberculosis. “Because it's had such an impact on humanity, there are a lot of myths around tuberculosis,” Anna says. “And there's a lot of different areas of medical research that have changed over time. There's this fascinating cultural story alongside the microbiological side.”  How was it transmitted? “Where there's dust there's danger,” warns a 1902 guide by the National Society for the Prevention of Consumption. At this time, tuberculosis was thought to be spread mainly by infected spit that dried on specks of dust. Invite a few tuberculosis sufferers into your home, let them spit on the floor, neglect to sweep for a few weeks, and eventually you could be stirring up clouds of death with your broom. Close up, I see the moth-like objects on the wall are actually tiny grey lungs. These are made from felt and dust, by Anna and people who have attended her interactive workshops. The advice was almost right in that tuberculosis can be spread by sputum, sprayed into the air by coughing, but dust could not spread tuberculosis. Drying out sputum droplets tends to kill the bacterium.  Today, thanks to whole genome sequencing, transmission of a disease can be more precisely mapped. I learn about this by examining a stand holding an old 'pocket-bottle for coughers'. The Blue Henry is an attractive blue glass bottle with a silver lid, intended to provide a safe and fashionable receptacle for sufferers to cough up blood in public. Like many of the artworks on display here, Anna has combined the past and present of tuberculosis on this object. The top is engraved with a patient transmission map, produced by the research of the Modernising Medical Microbiology (MMM) project. Today, the MMM scientists investigate deadly bacterial diseases by sequencing the genomes of the bacteria responsible. Using the sequences, they can identify which strains are responsible for disease outbreaks, and they can also map the transmission of an outbreak back to its source. The diagram on the lid of the Blue Henry shows how multiple people were infected by one person, who was in turn infected by Patient Zero, the first person to get the disease. Prior to whole-genome sequencing, unravelling the spread of a disease would have relied on a laborious process of interviews and piecing together likely infection scenarios. How was tuberculosis treated? There are fascinating items showing how tuberculosis treatments were marketed. 'REST... to beat TB' one medical poster declares, showing an improbably merry man as he lies in bed, resting off his tuberculosis. Resting was supposed to help recovery by lowering the breathing rate and giving the lungs of sufferers less work to do. Patients would also be shuttled off to sanatoriums in mountainous regions, where the air was thinner and thought to be better for the body. Anna tells me about an infamous Welsh mountain sanatorium, Craig-y-nos, where children were forced to sleep outside in fresh yet painfully frosty air, since this was thought to be another benefit. A jaunty magazine poses an attractive young couple under the headline, 'I had TB!'. Below this, Anna has arranged an innocuous little microscope slide of stained M. tuberculosis from sputum, the foe in question.  But there are also works based on more sinister tools. Anna explains that artificial pneumothorax- collapsing a lung- was once a common treatment. The idea was that collapsing the lung would 'rest' it, giving the lung a break to tackle its tuberculosis infection, and also starving the tuberculosis bacteria of oxygen. Around one third of tuberculosis patients were treated to this between the 1930s to 1950s, including the writer George Orwell. It's a toe-curlingly unpleasant idea, but Anna tells me that some small, recent trials suggest this antiquated treatment might help fight the modern rise of extremely-drug resistant tuberculosis. Sometimes medicine, like history, turns in cycles.  Textiles and dyes also play a large part in the history of tuberculosis. The maternity dress has been dyed with walnut husks, madder root and safflower. All common natural dyes, and all early treatments for tuberculosis. There's a vial and fabric-stains of Prontosil, the world's first 'sulfonamide' drug which could slow the growth of bacteria. It was produced by Bayer, today known as a chemical pharmaceutical giant, but who began as a dye manufacturer. Bayer's large chemical laboratories for producing dyes were perfect playgrounds to test out new chemical combinations. With ready supplies of coal tar, a by-product of coal production, a base for many dyes, and the bane of my childhood thanks to my dad's inexplicable fondness for coal-tar soap, many scientists tried to produce dyes to specifically target bacteria. Along with other useful products like aspirin, Bayer eventually produced Prontosil, and medicines derived from this bright red substance were widely used in bandages during WWII. It also had the side effect of dyeing the skin red. Anna has also found staining effects in modern treatments for tuberculosis, and she used the growth media for Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) (an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis used as a vaccine for TB) to add striking touches of pale blue to some of her artworks.  I also find out that Byron's vain wish to be pale and interesting would get a colourful update. Anna reveals that a modern antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, rifampicin, can cause the tears and sweat to turn orange. “In a way, they look like they have a nice tan,” she commented wryly. “So it's interesting how that link between fashion, appearances and tuberculosis has come about again.” Stories and the Sublime Anna is fascinated by objects that are tainted with the story of the disease, and has added more subtle combinations of old and new stories. The dress and tiny lungs are infused with the extracted DNA of M. tuberculosis. There is no danger that the DNA can harm anybody. But the DNA's presence in objects so close to me make me feel face-to-face with the bacterium itself, laid open before me. It is an intimate and respectful meeting, one without infection, disease, or pain. “My research into this exhibition began with conversations with scientists, and reading about the disease, and the more I did the more stories I found. The strangeness of everything, the stories, it's not really what people expect,” reflected Anna. “I'm definitely planning to take the work further, I think there's many more stories to be told.” She also runs hands-on workshops to explore the history of tuberculosis further, and sometimes people attend who have experienced old tuberculosis treatments first-hand.  Looking round the exhibition, I'm struck by how much it has filled in the cultural side of tuberculosis to me, something which was entirely missing when I studied the disease at university. In modern times we might easily think that only the scientific view remains now. With sophisticated technologies or new drugs, scientists work towards understanding cause, transmission, and treatment in ever closer detail. But cultural understanding of the disease is something uniquely human. And inspiration and appreciation of the microbiological world play a vital role in pushing scientific discoveries. Anna points out that microbiology is still a relatively new science. It was only a few hundred years ago that Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a textiles dealer, first saw microbes under his homemade microscopes. Van Leeuwenhoek was not a scientist, he was a textiles dealer used to examining thread counts under magnifying glasses. Yet he was inspired to explore the microscopic world after seeing pictures from Robert Hooke's 1665 book, Micrographia, with its detailed illustrations of textiles in the microscopic world. Van Leeuwenhoek went on to make a number of groundbreaking discoveries in science, and was always guided by his interest and appreciation in what he saw. “We're at a fascinating time when new technology is available and revealing more about the microbial world,” Anna said. She is also looking forward to exploring our relationship with other infamous bacteria, including artworks based on Staphylococcus aureus, the agent responsible for MRSA.  I asked Anna what she wanted people to go away from the exhibition with a sense of. “To me bacteria have this effect of the sublime. With all the effect they've had on humanity, but the fact that they're fascinating and beautiful too. Ideally I'd like people to come away from the exhibition with a sense of the bacterial sublime, to understand the sea of bacteria they're a part of, and that they're super-organisms containing bacteria. I'd like people to understand that.”  Additional Information Anna Dumitriu explains more about her artwork and inspiration in this film. Anna Dumitriu received a Leverhulme Trust Artist in Residence Award in 2011 to work with the Modernising Medical Microbiology project led by the University of Oxford, Nuffield Centre for Clinical Medicine, in conjunction with Public Health England. 'The Romantic Disease' exhibition is funded by the Wellcome Trust. The exhibition will be shown at the Waag Society until 27th July, and the Art Laboratory in Berlin from 26th September - November 2014. Links Anna Dumitriu's website: http://normalflora.co.uk/ Modernising Medical Microbiology website: http://modmedmicro.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ Waag Society: http://waag.org/en/event/romantic-disease-exhibition Further reading

|

AuthorNot quite a blog, but things that I have written. Please note - these writings are unedited, for the purposes of flexing my fingers, and no doubt contain grammatical errors and carelessness of expression I wouldn't allow in professional writing. Categories

All

Archives

June 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed