|

I dive at a shipwreck in Amed, shortly after dawn. Afterwards, stunned by the darkness and strangeness, I write this.

Lichen-encrusted, sprouting whorls of polyps and silicates. Pieces that have fallen into helpless decay. Velveteen fish with large unabashed eyes. Fins open and close in side-fan-flicks. The bumpheads are tooth-jutting, jaw-juttingly ugly, faces afixed in solemnical disgust. One huge one peels away from the flock to investigate us closer. Wringled green-grey dull skin. Moss-stained teeth. A jaw-wired-shut grimace. A hawksbill turntle, beak downturned in an old man's disapproval. Eyes flick and twitch to take us in. Fins scoop with praciced motion through the water. Crazy-paving dark brown, cracked choc ice coating over yellowed white. They wear scowls, these turtles. Everything underwater runs on slow motion. Flits of fish become miasma around the corals. Bluish water stains the ground brown and the corals yellowed. Its fins describe shapes. Nemo wrestles amongst the avid fingers of sea anemones. Breathe, breathe. Hold breath frequently at different volumes. Long to exhaule. Ears that refuse to pop, an eye that keeps filling with salt water. So many tribes, all around, everywhere. I need to know their names. From above, snorkelling, they look mindless. When amongst them, they look like life. Like nature. Nature eerily close. This doesn't happen above the surface. Drive in the darkness to the end of Amed, where a Balinese band play decent reggae covers. This is backpacker music and oddly hard to find in Bali. I eat a glass noodle salad, sip a cold beer, write this. Happiness tonight is live reggae, a scratchy singer's voice, and warm night air. Myopic eyes, contact lens fogged, but so all is sensuality, all is warmth. Human connection and my own sense of mobility and independence to take me to those places of connection is a continuous ouroboros I treasure. Do I have the fire? What is the fire now? The next day I snorkel through two bays in Amed. There is another shipwreck. Looking down, face plunged into the sea, I spy a thick and ugly face glowering below. I'm so surprised I yell into my mask. Thick-lipped and ugly, a huge black moray eel poking its head out. I turn, twist, peer through shoals of tiny flickering fish to see it again. It retreats slowly into the shipwreck. Cold and warm currents twine from underneath. In the other bay, I swim out so far I can scarcely see the bottom. I like doing this, because I'm not a good swimmer, never have been, so it's a treat to feel myself float and pull through the water without fear of drowning. I like feeling like a speck floating upon deep water, looking at a seabed so far below that I can't see it. It's like floating above a mystery. I find a tiny sunken temple closer to the shore. It would be pleasant to come out here each day to pray.  This was my favourite painting from The Art Book, a well-thumbed miniature bible to art which my brother had won for his work. I'm very pleased another writer / scientist has used it as a springboard to discuss the future of human embryo research in the US. When I lived in Amsterdam, I particularly enjoyed the Stedelijk Museum. There's a few wonderful Abstract Expressionist and Abstract pieces there upstairs - Cathedra, by Barnett Newman, a glowing wall of ethereal blue, and a Rothko containing a melting horizon. Yves Klein's moonrock alien blue landscape.

There's more to Abstract Expressionism than colours or chaos. Intent. Meaning. Emotions. Contemplation. But equally, part of the pleasure is the casual interpretation. And doesn't it all sometimes look like a big, glorious, mess? In science, colours are blooming too, abstract interpretations from rational intent. The Brainbow, shades of fluorescence used to tag not only neurones but fibres of the tongue, the stem cells of the small intestine. Stem cells producing the blood cells. A mess to the untrained eye, a precise labelling system to the scientific one. Beauty in the chaos of identification. The confirmation of a 100 year-old theory of Albert Einstein renders any blog or website posting pretty inconsequential. While the global news machine rolls on, champing out articles about Zika, Trump, refugee crisis, there is now a fervent subsection dedicated to reporting on the discovery of gravitational waves.

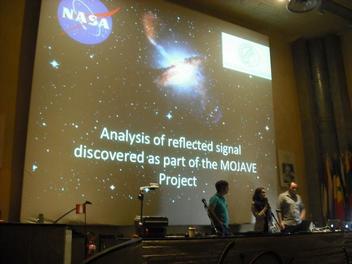

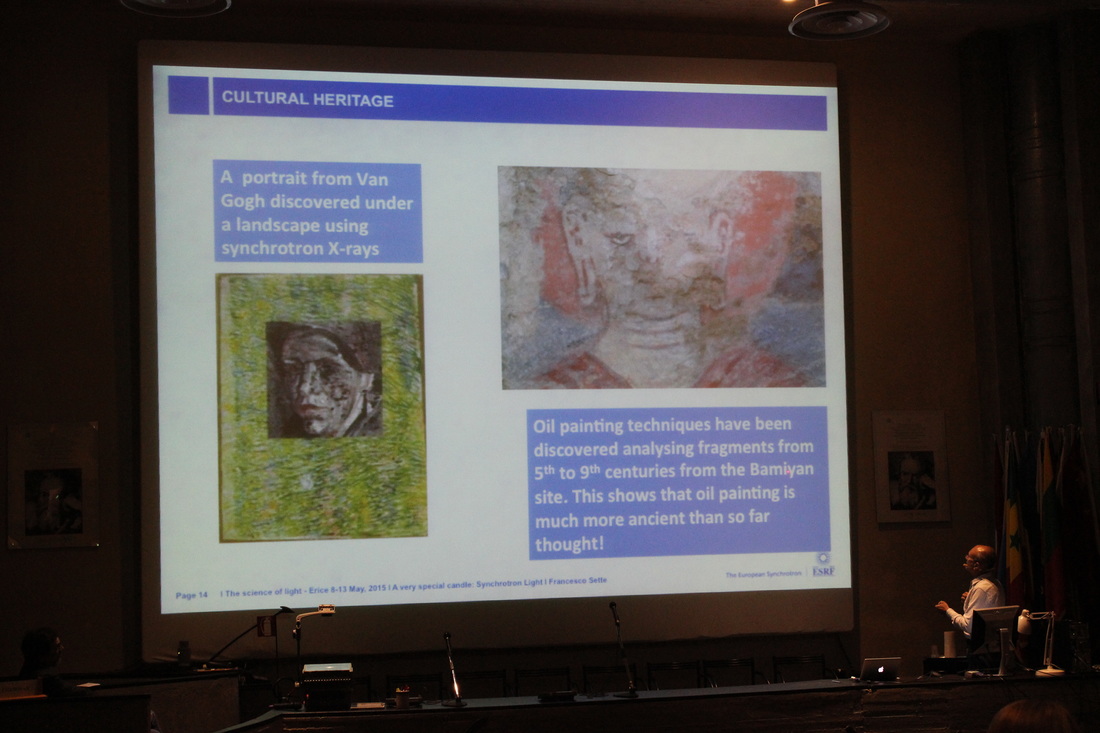

The import of the discovery is condensed into stylised, eye-catching and somewhat bewildering numbers. "The announcement is the climax of a century of speculation, 50 years of trial and error, and 25 years perfecting a set of instruments so sensitive they could identify a distortion in spacetime a thousandth the diameter of one atomic nucleus across a 4km strip of laserbeam and mirror," cries The Guardian. Why should we care? "While the political displays we have been treated to over the past weeks may reflect some of the worst about what it means to be human, this jiggle, discovered in an exotic physics experiment, reflects the best," says the New York Times Sunday Review, through the patient and poetic words of Lawrence Krauss. The New Yorker delivers an exciting narrative of the human stories behind the science. "David Reitze, the executive director of the LIGO Laboratory, saw his daughter off to school and went to his office, at Caltech, where he was greeted by a barrage of messages. “I don’t remember exactly what I said,” he told me. “It was along these lines: ‘Holy shit, what is this?’ ” XKCD delivers a swift dose of black line science snark, while NASA release a succinct dose of no-nonsense reporting. One UK tabloid takes a typical run at the story. "Einstein was RIGHT!" screams the Daily Mail. A thousand ways to tell this story. The science, now captured by observation and theory, enters the human narrative. You can read LIGO's richly detailed press release here, if you too would like to try your hand at capturing the "waves that propagate at the speed of thought." Day 2 of Erice International School of Science Journalism - Of Synchrotrons, SESAME, and Stars6/2/2015 Day 2 introduced some of us to a full night's sleep, and thus restoration of our full powers of intelligence, wit, humour and beauty. However this day also brought our remaining wayward fellow students to Erice, in much the same state of delayed-flight sleeplessness and jetlag as we earlier arrivals had been. The first talk was of 'a very special candle' – synchrotrons, as explained by Francesco Sette of ESRF. Synchrotrons are facilities that fire incredibly intense beams of light through objects. Synchrotron radiation is capable of illuminating research down to the atomic level, to explore the shape of molecules and to clarify the structure of viral ribosomes. This ability can also be used to piece together larger pictures, such as by revealing hidden van Gogh paintings, and reading the writing inside ancient scrolls from archaeological digs. Francesco led us through a potted history of synchrotron facilities, from the first tabletop-sized synchrotron of 1947, to the massive facilities that exist today throughout the world. Modern synchrotrons can generate radiation which is 100 million times brighter than the first described x-rays of 1885. Most facilities are distributed throughout Japan, the USA, and Europe. Later on, we would be introduced to a notable synchrotron being built in the Middle East. But next, Nicola Nosengo bade us to consider why light technology prevails, or fails. The invention of the blue LED in the early 1990s is considered so significant that it scooped a Nobel Prize in 2014. The invention of red LEDs, those red spots punctuating the everyday machines of our households and the glittering eye of HAL, did not win anything. For the combination of red LEDs, green LEDs and blue LEDs means that now white LEDs can be created. White LEDs are heralded as an efficient, energy and money-saving means to illuminate our environments and lifestyles. This steady improvement continues to uphold Haitz's Law, which predicts a steady increase in the light LED technology can produce against falling costs. This is the simple economic ideal, that better science leads to better technology at cheaper prices for all, and that more efficient, cheaper lighting will be a massive mainstay against global warming. But when our environment presents us with new benefits, we tend to change our behaviour to take advantage. This is Jevon's Paradox, quite simply, the message being that increasing fuel efficiency can increase consumption. So should we believe the hype about how beneficial LED lights will be? “Innovation in a single technology is one thing. Innovation in a technological system is another,” Nicolo warned. Similarly, just look at the impact that cars had on society, and our behaviour in this strikingly brilliant film... Luca Serafini delivered the second and final lecture on Extreme Light Infrastructure, focusing on the development of the ELI-NP laser in Romania. His first talk on ELI had been a crash-course in incredibly brilliant lasers operating at numbers and timescales of bewilderingly high and short scales. My brain was still trying to get to grips with these notions when it began learning about the ELI-NP laser. This laser will fulfil the nuclear photonics 'research pillar' of ELI, which means its research focus will be to explore and manipulate atomic nuclei. That's the easy part. The difficult part to comprehend is that this will be a uniquely powerful laser at the very forefront of research, producing the shortest and most powerful laser flashes, such that the acceleration of photons achieved over 10km of accelerator can instead be generated from 1cm pulses of plasma. The mechanism by which this is achieved emulates the gamma-ray bursts of distant galaxies, the brightest radiation events in the universe. Luca introduced a present and near future where relativistic optics become ultra-relativistic optics and eventually QED optics. The words he used dipped in and out of my uneven grasp of self-taught physics like the hazy plot of a badly dubbed film. My consciousness was rooting through slightly abandoned reserves of my brain, hurriedly seeking more mental yardsticks for scale and wonder. I stared at a helpful analogy for electrons surfing waves to understand this high-level physics. It was reassuring in its simplicity, a pictoral pacifier. Again, how helpful analogies can be used to translate physics for non-mathematicians, I thought, reassured. Sketching out futuristic ideas for high-energy lasers, such as to scan sealed containers and detect nuclear fuel, Luca reflected that the ELI-NP laser is also a prototype, at the front-line of technological progress. How its technology will come to be adopted and refined by industry remains to be seen. We went out to seek lunch in Erice, and became entangled in the curious nether reaches of Sicilian time. It is an elastic and abstract concept that swept us up, fed us (some of us / eventually / not at all) and deposited us for a necessarily late-starting seminar hosted by Open Knowledge. Open Knowledge is a non-profit organisation who promote open data. That's the generic nutshell description, but the seminar conveyed richer and better messages to us. Open Knowledge ask us to be aware of our own power as data journalists - curators of the sea of available open data. Data journalism can open up specific perspectives in a topic, as well as uncover new stories. The eponymous handbook can be found here. Jonathan Gray and Liliana Bounegru showed us examples of a range of data curations, with impacts ranging from the entertaining - The Most Googled Thanksgiving Recipes by US State presents a surprising selection of American cuisine - to the ever-prescient – Climaps reveals geographical preparation to climate change – to the brutally sobering – The Migrants Files meticulously documents the loss of 29,000 human lives. Open Knowledge have also created the Panton Principles specifically for open data in science, to help scientists to make data from their studies available for public use. Afterwards, we planned our own data projects. The topics on our mind proved to be drones, anti-vaxxers, and science engagement. Francesco Sette's talk showed us the distribution of synchrotrons throughout the world, which are mainly distributed throughout Japan, the USA, and Europe. But Giorgio Paolucci introduced us to SESAME, the first synchrotron in the Middle East. SESAME is a research facility that will both augment and unify the work of scientists from multiple Middle Eastern countries. Through political tensions and regional conflict, the “common language” of science is the focus of the developing SESAME facility. After another dinner, the evening was finished with a night-time stroll to the castle where Larry Krumenaker, astronomer and science journalist at University of Heidelberg's Institute of Theoretical Physics, introduced us anew to the stars. Little had I realised that the tools for measuring degrees of latitude, had forever been located at the ends of my wrists. Larry introduced us to various memorable stars and bodies of the night sky, pointing out useful features including Venus, silvery siren, the bright star Regulus, the constellation of the Lion which also happens to look like a mouse, and the North star. And that was Sunday. Here, have some more Marsala wine. Day 1 of Erice International School of Science Journalism - Of Light, Late Arrivals, and Lasers5/14/2015  Copyright 2015 Emiliano Feresin @emilianoferesin Copyright 2015 Emiliano Feresin @emilianoferesin There is some light we definitely do not need. Light pollution, melting away the view of the stars. Drivers who leave their foglights on while approaching you at high speeds. Flickering fluorescent lights when you're stuck working late in the office you don't particularly like anyway. I would also like to nominate the unexpected light at Rome Fiumicino airport on 7th May 2015. This was caused when a fire chewed through a baggage hall in Terminal 3. There were no serious injuries, but the travel plans of thousands of international travellers were duly consumed in the process. Surely, most terrible of all, was the damage done to the travel plans of a particularly special group of international science communicators. Some slipped through unscathed. Others arrived in the early hours of Monday morning, bleary-eyed and lurching through the darkness of the Sicilian night. Others lost entire days in a nadir of intercontinental time zones, batted back and forth between delayed flights, cancelled flights, and interminable airport stays. But one by one, our heroes eventually made it to Erice International School of Science Journalism 2015. Following this shaky start, we were all extremely appreciative to arrive to the lecture hall and receive Fabio Turone's welcome speech. We were also grateful for the inclusion of coffee breaks on our schedules, liberally provided so that we could consume plentiful cups of the magical juice of wakefulness. The first day began with a talk by Luca Serafini, Research Director of INFN – Milan. (He is also the star of Extreme Skiing on Orobie – mind you I didn't have to delve far to find this fact, it's on his INFN profile...). With his talk about the Extreme Light Infrastructure, he launched us into the 2015 course. His talk detailed the different research areas of ELI and the science of lasers. He led us gently into this world of high energy photons by weaving in beginning references to Blade Runner's poetic androids and mysterious C-beams to illustrate the great challenge facing him. How could a physicist explain physics without using the language of mathematics? And for that matter, how could C-beams be visible in space, if light cannot interact with itself, which also topples the hopeful hearts of millions if it destroys the fantasy of light sabers? But I can assure Luca that he succeeded in his endeavour. I know now, for example, the definitions of power, intensity, and brilliance, the reason why the sky is blue, and that there is a 300 TW laser FLAME at INFN. It has a greater brilliance than the Sun. Just... just as a laser pointer does... After this slice of heavy science came Fred Balvert of Erasmus MC Rotterdam. Through his talk he invited us to discuss the intentions and order of questions to consider when promoting science. I think one of the easiest forms of science communication is explaining research science in clear or interesting ways. Indeed, mediums such as television often focus heavily on translating and transmitting that interest of research into full-blown wonder. I'll just leave this here as an appreciative nod to the wonder, and this here as a cautionary tale that science, as entertainment, is a two-edged sword. But how can we best communicate the relationship between research, society, and industry to the public? Scientists do not toil alone in their labs, but are funded by and responsible to society. But who can see how research might benefit society? CERN and Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web, but they did not have to describe this intention in several rounds of detailed grant applications to get there. (Of course, it is really the fault of scientists for not inventing that useful time-travelling machine yet). Science is both fuelled by, and the food of modern industry and economics. However faceless pharma and large corporations do not inspire trust easily. The EU has specified that all funded research projects must contain a plan of communications. Perhaps difficulties can arise when scientists must apply opinions and commentary to issues of science, since this contrasts with the objective, results-focused approach of the scientific method. A journalist's role is to describe, monitor, comment, and challenge issues. As science journalists, we bridge this gap. Our first coffee break promised refreshments to combat the lack of sleep. However nothing could be more effective for a tired mind than this stunning view from the terrace.  Copyright 2015 Nikita Mehta @athem_atikin Copyright 2015 Nikita Mehta @athem_atikin In the afternoon, the school became even more interactive as we practiced preparing for a media conference on striking scientific discoveries. We took opportunities to become experts, science spokespersons, media managers, shrewd journalists, astrologers and tabloid hysterics. It was interesting to see the differences in approach from each group, and to probe the fine balance between speculation versus objectivity when reporting a science controversy.  I also became one of the world's most foremost, and indeed least qualified experts in radio telescopes. You never know where you'll end up in life. Later that night, I also briefly became much rounder and slower after several courses of dinner. I'm British and I'm not used to receiving multiple courses of starter, pasta, meat, and dessert as a your typical, run-of-the-mill meal. Thankfully I did adapt, but now I'm in withdrawal. This was followed by several cups of Marsala wine in the Marsala room. The positive correlation between cups of Marsala wine and enjoyable verbosity of conversation is very clearly delineated, but nonetheless, we continue to conduct the field research. However, I must share my best discovery, which is this: one part sweet Marsala wine to two parts dry Marsala wine.

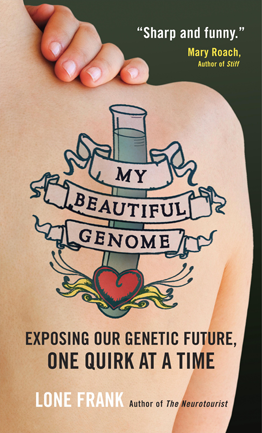

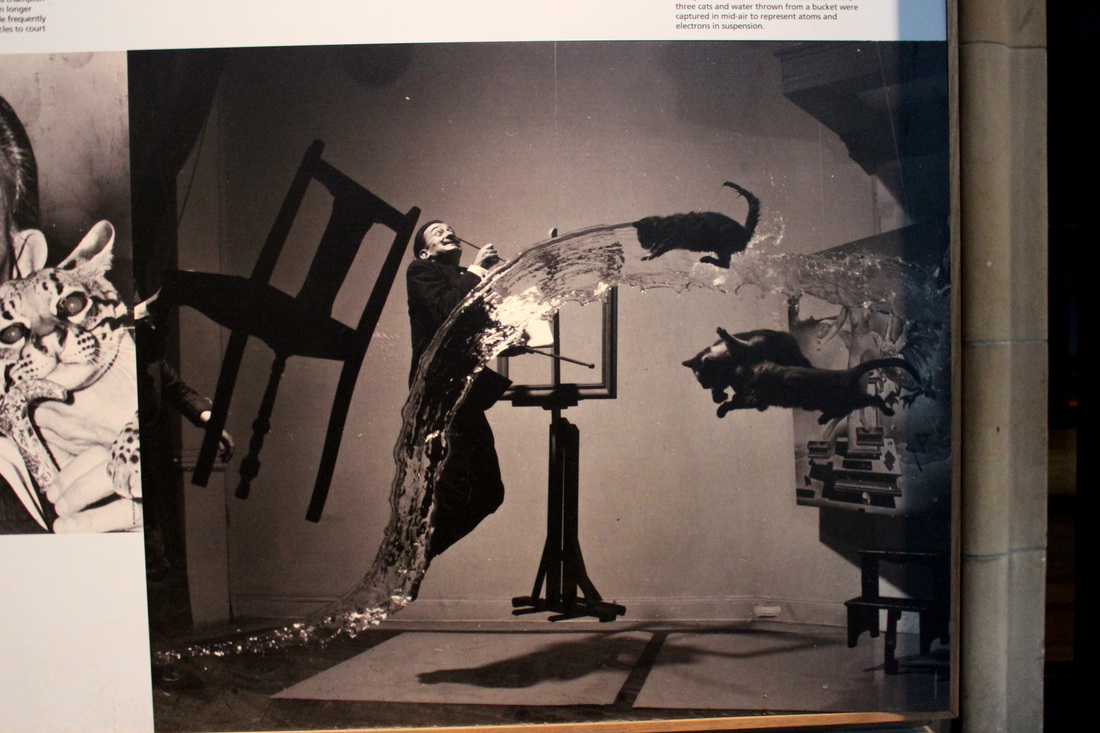

You're welcome.  A book I'm re-reading lately is My Beautiful Genome by Lone Frank. Essentially, I recommend it, and here's why. My Beautiful Genome is an account of Lone Frank's journey into finding out what our genomes can say about what, who, and why we are. Or it could be more accurate to say, what scientists thus far understand about the what, who, and why. It's just over 10 years on since the Human Genome Project and Celexa laid out the human genome in its confusing glory- 23 chromosomes, 30,000 genes, 30 billion base pairs- and thanks to techniques, technology and t'internet, times have changed a lot since. The original human genome took 3 billion dollars and 13 years to complete. Nowadays a human genome can be sequenced for almost 1000 dollars in a few hours. So all right, supposing I have a spare 1000 dollars and connections to a world-class lab. Should I get a proof of my own molecular recipe? Lone, a Danish science writer, sets out to see what can be seen. The easy narrative of the book follows her physical journey to various labs and doctors, countries and universities. It's low on jargon and enjoyable to read, a science travelogue imbued with Lone's own descriptions and inner thoughts, which add a hint of narrative drama to the interview scenes. James Watson gazes at her from thickly bespectacled "golf ball eyes" that are nonetheless "clear without a hint of the common confusions of old age". Lone admits her own faults, such as a blunt personality she feels proud of, while a friend disagrees- "It's cruel!". She describes her fear as she waits to find out if she has BRCA mutations that would show a susceptibility to breast cancer. She reflects openly on mental illnesses in her family and her own experiences in it. She is a likeable, cynical investigator. The short answer from this book is that genetics still can't reveal much about the average person. However, there are plenty of hints. I daresay that still holds true. This book was published in 2010 so in scientific terms it's a little out of date, especially with a field as fast-moving as molecular biology. Still, I found plenty about the business and politics of genetics that I hadn't been aware of. And Lone's journey contains many interesting tidbits from various research areas that summarise how complicated genomes are. For instance, is human intelligence inheritable? Sure, studies indicate that 80% of a person's intelligence is down to genes. Which genes? Don't know! 20 years of study failed to find any 'IQ genes'. Best case scenario? In another few years, the researchers might whittle it down to a few hundred genes that explain 3-5% of a person's intelligence. Another surprising fact is that where some genes are concerned, such as a gene that affects how likely you are to get diabetes, it matters who you inherited them from, your father or your mother. You could be more likely to get diabetes if you inherit this gene variant from your father. But you are less likely to get diabetes if you inherit this gene from your mother. Lone explores the services of a few different companies and research schemes. The Genographic Project can tell you about your ancestry as well as answering bigger, older questions about where early humans lived and moved to. Then there is the big, attractive question of genes and health. Can your genes predict what diseases you might be prone to? Lone receives a few interpretations of her genes. She has variants that increase her risk of lung and skin cancer, worry and depression, a small hippocampus and obesity. She also has variants giving her higher resistance to malaria and TB. Lone admits to a few depressive episodes. On the other hand, Lone has always been slim, has a normal-sized hippocampus, and has never had skin cancer. Genomic medicine is still in its infancy, a mix of ambiguity and intrigue. This book cannot be used by a reader as a manual of certified gene variants, but it is scattered with interesting insights from the modern scientists who are wading through the legacy of the Human Genome Project. Should people get their genomes assessed for probability of diseases? The research continues. Governments such as the UK are funding genomic medicine centres. There's also a scramble of entrepreneurship and commercial ventures. Companies like 23andMe are hoping to be the new Microsoft of personal genetics, offering direct-to-consumer genomic testing. Another genomics motion, deCODE is cataloguing the genomes of most of Iceland. But to me, it seems most of these companies do not provide value for money or time of thought. Studies such as by Erasmus University have shown vastly different results in the answers of your genome analysis, depending on which company you use. Processing errors have happened, resulting in some alarming results and alarming scenes at the consumer's homes. A ruling by the FDA has put a halt on health screening by 23andMe in the USA, but the company is branching out in the UK and Canada. How long should it be before genomes screening for health is carried out, to prevent misinterpretation and misunderstandings? "It is inevitable that we will come to use it. It would be criminal to decide that people must not use this knowledge before we know how it will affect them biologically, psychologically, and socially," Kari Stefansson, founder of deCODE, argues to Lone. He believes the best way to treat disease is to prevent it, and all would agree. How far back can we prevent disease? Armand Leroi, a geneticist at Imperial College London, has judged the risk of finding disease by screening embryos for known mutations to be around 1 in 256. Lone points out that this level of risk is sufficient to justify cervical and breast cancer screening. Is the stage being set for large-scale embryonic screening? Then there's the popular topic of how genes influence our behaviour. It's the classic nature vs nurture debate, a popular topic among biologists, psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists, parents, teachers, politicians, everyone... This debate is continually updated with increasingly detailed genetic data, and occasionally thrown to the public forefront by popular books like Richard Dawkins's seminal book, The Selfish Gene. His book launched a thousand debates about whether we were all fleshy vehicles steered by a control-box of self-replicating genes. "As soon as people hear the word 'heredity' or 'genetic', it immediately gets transformed into 'unchangeable' somewhere in their mind, and that is not the message at all," warns Gitte Moos Knudsen, research director at Center for Integrated Molecular Brain Imaging at Copenhagen University. Lone has gone to see her to see how a personality questionnaire, brain scans, and her genes may be linked up. You'll have to read the book to find out what she discovers. But there's an intriguing mention of a study indicating a genetic basis for differences in behaviour between two major cultures. Gitte also points out that even ostensibly negative genes- like a variant linked to 'oversensitive' behaviour- must give the owner some advantage. Else why would so many people still have this gene? The media gleefully reports behaviour-gene associations that make the best stories. A discovery of an 'infidelity gene', for example. But there is still no consensus on how to divvy up their own behaviour between nature and nurture, and I suspect there never can be. I think we do have free will. We also have brains housing that free will. Brains are made from both genes and general living. There will just be new and interesting ways to look at our brains from a genetic standpoint. "People cannot stand the complexity of a nuanced problem. There is a huge desire to lean back and say, 'It's my genes, it's not my fault,'" sighs Kenneth Kendler, a psychiatric epidemiologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, during a discussion on genes, growing up, and psychology. He and Lone discuss the difficulty of linking a person's psychology to their genes. There is no single gene variant responsible for causing Alzheimer's, for instance. Most diseases will involve multiple genes acting in ways scientists still don't understand. The same issue will apply for behavioural traits, or psychiatric conditions like depression. But studying behaviour from a genetic standpoint will help build up the overall understanding. Kenneth mentions the serotonin hypothesis as an example. The major theory is that depression is caused by low levels serotonin, a molecular messenger, in the patient's brain. Drugs that alleviate the symptoms of depression affect serotonin levels. But scientifically speaking, it's not known why this works. There is no 'normal' level for serotonin throughout the brain. Lone reveals a rather striking quote from David Healy, a psychiatrist specialising in antidepressive remedies. "The theory that serotonin levels are the cause of depression is as well founded as the theory of masturbation causing insanity." This doesn't mean we should toss out our antidepressants or stop the self-love, though. It means that the picture is complex and genes are part of the complexity. Studying genes in detail could also provide a new way to monitor psychiatric therapy. "Psychiatrists used to ask people endless questions about their mothers, as if we could make good predictions on that basis. At least, genes are objective," said Daniel Weinberger, neuroscientist at NIH. And it does not have to stop at what genes each person has from birth. Epigenetics adds another layer of complexity. Studies have shown that life experiences can alter how your genes behave. In a nutshell, this is caused by life adding molecular labels onto your genes. Moshe Szyf, epigenetics expert at McGill University points out benefits of tracking the labels. "If we know the epigenetic signatures and markers - for abused children, for example - we can design behaviour therapies, talking therapies, and study whether they work. Determine whether they remove the markers in question." This hints that future psychiatry could be a synergy of epigenetics, genetics, behaviour and therapy. There's also a scramble of entrepreneurship to make money out of genes and love. GenePartner claims it can help you find your ideal social and biological partner. To fall in love may lead to having children, and children are the combination of you and your partner's genes. Do genes secretly steer our choices? Can knowing our genes help us choose the best partners? The enterprise is based on a few scraps of intriguing science. Immune system is coded for by genes, and everyone (save clones and twins) has a unique set of immune genes, known as HLA genes. Zoologist Claus Wedekind noticed that many animal species sniff out mating partners who have the biggest differences in HLA genes from their own. The suggested reason is that such pairs produce offspring who have particularly varied immune systems, and are more likely to resist local germs. This tendency has also been noted in humans, in a handful of studies, starting with Wedekind's own study in 1995. Statistically speaking, women prefer the smell of men with the most different HLA genes, marriage choices in some communities appear based on this effect. It's an exciting thing when pieces of scientific evidence can be tied together with evolutionary reasoning. Once I explained to a new boyfriend that given our respective ethnic backgrounds, our HLA genes were likely very different, ergo another reason why our relationship was destined to succeed. I can't understand why he found this so amusing. On the other hand, Craig Roberts, behavioural ecologist at University of Liverpool warns, "It's a scam. We're not at the stage where we can say HLA genes make a practical difference." There are other factors to consider here than the immune system, and a few other studies go against the varied HLA connection. Again, statistically speaking, studies show that people tend to prefer faces of others who have similar HLA genes. And has anyone studied if human children from varied HLA matches are actually better off? Many people are afraid of genetic discrimination in the future. This book goes a long way to explaining why this is unlikely to happen by describing the existing science and viewpoints. Of course it remains a risk, which is why people need a gene lexicon containing terms like 'risk' and 'potential', rather than terms like 'good' and 'bad'. Towards the end of the book, Lone discusses how it is thought both biology and sociology- a new 'biosociality'- needs to be a large part of the consciousness of the future. Understanding of genetic difference may show where lifestyle changes could have the greatest impact. Those with predispositions to stress from poorer backgrounds may benefit more from mentoring, or those at greater risks of certain illnesses will need more assistance avoid these things. It will require a sensitivity of thought by any politicians passing legislation, and a malleability of 'nature vs. nurture' thinking on everyone's part. Lone's view is that in understanding more about genomes, we will also come to understand and appreciate diversity. So at the end of another enjoyable read, would I want my genome sequenced? I certainly would not be afraid to have it done. Will I have it done? I'm in no hurry. I don't think the science is well understood enough yet from an academic perspective to get any useful results. I'm not yet inclined to approach a company to interpret my genes. But it's getting closer, and I suppose, then, so am I. One day, I'll learn more about myself. It's nice to have such things to look forward to. My Beautiful Genome - a TED talk by Lone Frank I'm learning new things about Salvador Dali. Earlier this year, I visited the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, and discovered a room full of Dali paintings which I had never seen before. When an artist is as famous and familiar, like Dali, they have assumed a public identity through their most famous and familiar paintings. The distintegration of time, the fragile stem-legged elephants haunting desolate yet colourful deserts, tigers leaping after flowing cloth. I've love the detail of Dali's Old Master-style, even and especially the way it slightly repulses me in its hyper-real depiction of unpleasant drooping textures and Surreal disturbia. I'd never seen his painting of a vision of Africa, lushly dark in black and red, showing the painter poised in the corner, drawing up his vision like a magician gesturing magic. Or his painting, 'The Great Paranoiac'. Feverish, fainting figures stumble across the canvas, reaching out weakly for support. A multitude of small bodies and stories make up the shape of Dali's own face, haunted and flickering. Looking into the painting, my eyes flicked back and forth between the different ways of seeing, the shivering figures and the great bowed head. It's a painting which personifies mental illness with ruthless clarity. So, Salvador Dali, surrealist and psychologist. But recently I found out that much more science permeates his work. At the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum hangs 'Christ of St John of the Cross'. The painting is based on a 16th century drawing by St John of the Cross, a Spanish friar. In the painting Christ is pressed against a cross, suspended in darkness over a stretch of shimmering clouds and skies, sculpted sandy horizon. Dali based his painting on two dreams he had, and built physics and mathematics into its composition. His first dream gave him an idea for the shape of the figure and perspective, based on his imagination of the nucleus of an atom. Dali had studied physics and dreamt dreams of atoms in the wake of WWII. The discovery of the atomic nature of the universe held a special meaning for him.  "In 1950 I had a cosmic dream in which I saw in colour this image, which in my dream represents the nucleus of the atom. This nucleus afterwards took on a metaphysical meaning. I consider it to be the very unity of the Universe, Christ." He used the mathematical theories of Luca Pacioli to work out the striking proportions of the painting. Outside the room holding the painting, I also spied this intriguing photograph, 'Dali Atomicus'. It displays a remarkable timing of coordinated chaos. I wonder how many cats had to be flung. After I came home and did a little searching, I found out that 'Christ of St John of the Cross' is only the tip of the iceberg. There is much, much more to find out about Dali and his inspiration borne of maths, science, and religion. |

AuthorNot quite a blog, but things that I have written. Please note - these writings are unedited, for the purposes of flexing my fingers, and no doubt contain grammatical errors and carelessness of expression I wouldn't allow in professional writing. Categories

All

Archives

June 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed